Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

9 min read

Before the emancipation of the Jews of France, many advocates for equal rights portrayed themselves as friends of the Jews while actively promoting the eventual erasure of everything Jewish.

In 1775, a group of Jews in the French town of Thionville in Metz sued the town administration and its merchant guilds for denying them the right to set up a printing business. At the time, French Jews in pursuit of livelihood were limited by many restrictions, but they intended to argue in court that a royal decree of August 20, 1767, which permitted both foreigners and French citizens to set up certain businesses, should apply to them too. The Jews hired a non-Jewish lawyer, Pierre-Louis Lacretelle, to help them make their case.

Lacretelle indeed argued on behalf of the Jews. A closer look at his argument shows that he was motivated not by love for Jews but by the desire to see Jews as a nation disappear through assimilation.

In court, Lacretelle openly admitted that he believed that Jews engaged in deceitful business practices and unethical money lending. However, he blamed Christian persecution and the restrictions on commercial activities for Jews’ economic “vices.”

He proposed the following solution1: “Let us open our cities to them; let us permit them to spread throughout our land; let us treat them if not as compatriots, then at least as men.” In addition, Lacretelle argued for legislation preventing Jews from engaging in moneylending: “Let us force them to change, just as we change their condition2.”

Lacretelle claimed that once Jews were granted equal opportunities, they would also “adopt our manners and our laws, and willingly place themselves beneath our happy yoke3.” Moreover, out of gratitude for the opportunities granted them, Lacretelle looked forward to “the fulfillment of the hopes that still separate them from our religion4” – in other words, conversion of the Jews to Christianity.

Professor Maurice Samuels, chair of Yale University’s French department, in his book The Right to Difference: French Universalism and the Jews distinguishes between different types of assimilation: economic, political, cultural, and religious. He summarizes Lacretelle’s views:

Lacretelle requires economic assimilation of the Jews and recommends legal measures to “force” the Jews to change their business practices. He expects cultural assimilation… and political assimilation… but does not require them. Finally, he hopes for religious assimilation—that the Jews will one day become Christian—but puts this possibility off into a more distant future and sees it as entirely voluntary on the Jews’ part: the Jews might eventually convert out of gratitude for kind treatment.

Lacretelle only offered his friendship on condition that Jews assimilate, at least to some extent. In that sense, he was not much different from Christian missionaries who befriend Jews in an effort to “save” them.

Pierre-Louis Lacretelle

Pierre-Louis Lacretelle

Professor Samuels writes5, “In Lacretelle’s plea on behalf of the Jews of Metz, we find the essence of the regeneration ideology that offers Jews rights but demands, or expects, assimilation in return.”

The concept of “regeneration” – reforming the Jews to make them suitable for French citizenship – gained popularity in the following decades. It remained the subject of public debate as late as Napoleon’s reign. Though not every proponent of emancipation expected the Jews to convert to Christianity, many of them wanted to see Jews assimilate to some degree.

In 1777, a public scandal drew attention to the Jews. François Hell, a judge in Alsace, France admitted to forging false receipts for the local peasants, claiming that the holder of receipt had repaid the money he’d owned to a Jew when in reality, the debt remained unpaid.

Though the Jews of Alsace were the victims, they were put on the defensive when Hell authored an antisemitic pamphlet, Observations of an Alsatian on the Present Affair of the Jews of Alsace, igniting antisemitic sentiments.

A Jewish shopkeeper with two clients, ca. 1700s, by Jan van Grevenbroeck. (Museo Correr, Venice, Italy, Bridgeman Images.)

A Jewish shopkeeper with two clients, ca. 1700s, by Jan van Grevenbroeck. (Museo Correr, Venice, Italy, Bridgeman Images.)

A German historian and writer, Christian Wilhelm Dohm, came to the Jews’ defense. His book, On the Civil Improvement of the Jews, argued for equal rights for Jews. Originally written in German, the book appeared in French translation in 1782.

Purportedly advocating for the Jews, Dohm expressed very negative sentiments about them. Professor Samuels summarizes Dohm’s views6:

Like Lacretelle, Dohm would stress the Jews’ negative qualities, their economic backwardness and social isolation… Dohm viewed the Jews as an economic liability because they produced nothing. He characterized the Jews as a nation of middlemen whose usurious practices sapped wealth from honest farmers and artisans. This economic backwardness, moreover, had a negative effect on their moral character and prevented the Jews from feeling a sense of civic duty…

Dohm blames Christian oppression through the centuries for the Jews’ degraded state, and he describes this history of oppression in detail, emphasizing how Jews had been forced to play the roles of moneylender and middleman because of their exclusion from other, more productive professions.

Dohm’s proposed solution was to remove restrictions on the Jews and allow them to own land and to participate in guilds. Samuels concludes7, “This new freedom, he hoped, would improve the Jews’ morality and foster a sense of solidarity with non-Jews. His goal was ‘civic improvement,’ which is another way of saying regeneration.”

Significantly, unlike Lacretelle, Dohm did not expect the Jews to eventually convert to Christianity. The reforms he advocated were purely in the political and economic realms.

Christian Wilhelm Dohm

Christian Wilhelm Dohm

In August 1789, the revolutionary National Constituent Assembly proclaimed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, stating8, “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on considerations of the common good.”

However, Jews soon discovered that the newly proclaimed equal rights did not apply to them. They immediately petitioned the Assembly for their own rights. The Assembly established a committee to consider the question.

One of the most vocal proponents of equal rights for the Jews was Abbe Henri Jean-Baptiste Grégoire. Two years prior, he was one of the three winners of the essay contest, sponsored by Metz Academy, on the topic Is there a way of making the Jews more useful and happier in France?

In his winning essay, along with advocating for equal rights, Grégoire had explicitly called for the assimilation and conversion of the Jews9:

Complete religious liberty granted to the Jews will be a grand step towards their reformation; and, I will venture to affirm, towards their conversion; for truth is never persuasive, but when it appears in the garb of mildness… By encouraging the Jews, they will insensibly adopt our manner of thinking and acting, our laws, our customs, and our manners.

However, in Grégoire’s Motion in Favor of the Jews, submitted to the Constituent Assembly, he relaxes his requirements, no longer tying Jewish religious differences, such as dietary laws, to political rights: “And moreover what does this dietary difference matter to political tranquility?10” He even admits that Jews, despite their “vices,” “also present reasons for us to praise them11.”

An especially heated debate took place in December 1789. Another advocate for equal rights for the Jews, Stanislas Marie Adélaïde, Comte de Clermont-Tonnerre, gave what later became known as the Speech on Religious Minorities and Questionable Professions.

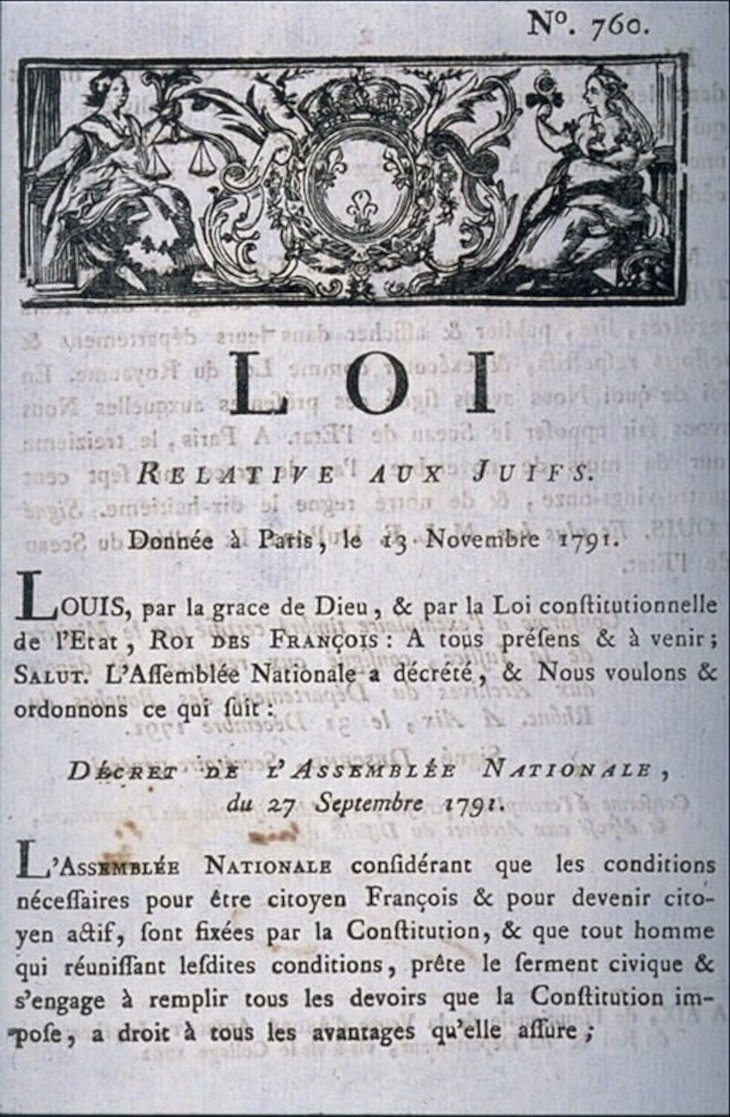

Decree proclaiming the emancipation of the Jews. Musée d'art et d'histoire du Judaïsme, Wikimedia Commons

Decree proclaiming the emancipation of the Jews. Musée d'art et d'histoire du Judaïsme, Wikimedia Commons

Though Clermont-Tonnerre, like his predecessors, criticizes the Jews for moneylending, he blames the restrictive laws and proclaims12, “Let them have land and a homeland and they will no longer lend: there is the remedy.”

He continues the new trend of no longer seeing religious and cultural differences as an obstacle to French citizenship. Though he criticizes the Jews for being a nation apart, he admits that neither their choices of with whom to share a table or of whom to marry are against the French laws.

However, Clermont-Tonnerre speaks strongly against Jewish self-government13: “To the Jews as a nation, nothing; to the Jews as individuals, everything… Their judges should not be recognized, they should only have ours; no legal protection must be given to the maintenance of the so-called laws of their Judaic corporation; there must not be any political body or order within the state; they must be citizens individually.”

Another proponent of equal rights for Jews was Maximilien Robespierre, the famous French revolutionary. Though he, like the others, blames persecution for Jewish “vices,” the idea of regeneration is not part of his argument. For him, granting Jews equal rights is simply the just thing to do: “I think that we cannot deprive any individual . . . of the sacred rights that the title of man bestows upon him14.”

Professor Samuels posits that the French Revolution was the turning point in the debate about the legal status of the Jews. The revolution shifted the focus of the debate from the Jews themselves to the definition of a French citizen and who could qualify as such.

But this shift was by no means the end of discrimination against Jews. Most participants of the December 1789 debate opposed granting Jews civil rights.

The debates continued in the following years, as the idea of Jews becoming equal citizens permeated the French revolutionary environment. Finally, just before the Constituent Assembly dissolved, it issued the emancipation decree for the Jews in September 1791.

Postcard featuring an old synagogue in Thionville, Metz, France

Postcard featuring an old synagogue in Thionville, Metz, France

Jews finally did become French citizens but they continued to be targets of antisemitic rhetoric. The “Jewish Question” was far from resolved when Napoleon raised it again 15 years later.

Whether Napoleon was a friend or foe of the Jews has long been debated by historians, but one thing is clear – not everyone who has claimed to advocate for the Jews was proven a trustworthy ally.

Contrast the French Revolution to the American revolution. Our Constitutional convention we put in our Constitution that there would no religious tests for public . Washington letter to the Newport Synagogue shows that the government gives to “ bigotry no sanction to persecution no assistance “.

Nice words, and very likely sincerely meant when they were said, but they're clearly inapplicable to what's happening in the USA today!