Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

7 min read

Four inspiring lessons I learned while rendering a unique Yiddish-language memoir into English.

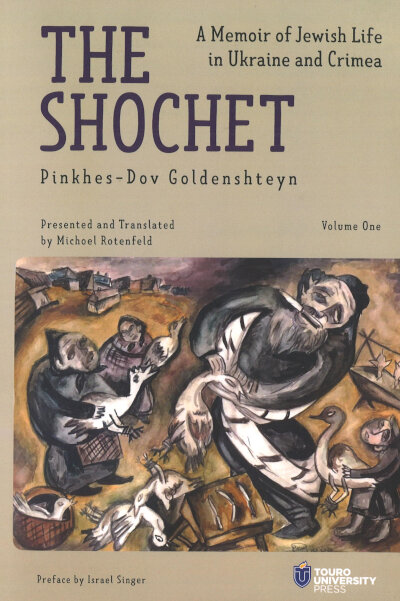

As a historical researcher and a student of autobiographies, I’ve read scores of life stories. But for sheer drama—not to mention moral inspiration—I haven’t found any that match the recently-published memoir titled The Shochet: A Memoir of Jewish Life in Ukraine and Crimea by Pinkhes-Dov Goldenshteyn (1848-1930). I was privileged to translate Goldenshteyn’s original Yiddish-language work, the first volume of which was recently published by Touro University Press, with Volume Two due out in October.

Goldenshteyn worked as a shochet, a kosher slaughterer, for over 40 years. In order for someone to become certified as a shochet, an individual must master challenging texts, train and intern under experienced slaughterers for little or no money, and pass a certification test with all of its political challenges. A shochet must show himself to be a person of competence and compassion, and Goldenshteyn possessed both in abundance.

What makes Goldenshteyn’s life story stand out from so many others? Authored by an Orthodox Jew in late-19th century Ukraine and Crimea, the book gives readers a unique first-person account of life in the classic shtetl of old-time Eastern Europe. It sheds brilliant new light on the complex religious and social milieu of the time and the harsh economic realities that poor, small-town Jews faced in that era.

The book is a unique first-person account of life in the classic shtetl of old-time Eastern Europe that sheds new light on the complex religious and social milieu of the time and the harsh economic realities that Jews faced in that era.

Even more, The Shochet provides a fascinating window into its author’s own inner spiritual life, demonstrating the power of his Judaism to sustain him throughout a turbulent life filled with trial and tribulation. A master storyteller writing in a rich Yiddish, Pinkhes-Dov—or Pinye-Ber, as he was known—succeeds in drawing the reader into his story to share in his joys and heartaches and to experience along with him the succor that he draws from a wellspring of deep trust in God.

Born in Tiraspol, Ukraine to a Hasidic family, Pinye-Ber’s life experiences take him throughout the far reaches of Ukraine, Moldova, Romania, and Belarus. He loses his mother at age five, his father at age seven, and his only brother a year later. Barely able to feed themselves, his sisters send him to live with a series of relatives and strangers who prove incapable of dealing with this smart and rambunctious boy. With no one to take responsibility for him, he is frequently beaten and cheated.

Despite experiences like these, and the added challenges of destitution and hunger, he succeeds remarkably in retaining a sense of humor about his hardships and a positive attitude. He eventually becomes a shochet and assumes a position in that field in the Crimea in 1879. There he faces further struggles until he immigrates to the land of Israel in 1913, where he lives until the end of his life.

When I first began this project, I did so from the perspective of a translator. I engaged in intensive historical research in order to ensure that my rendering would be as accurate as possible. I also wrote a 75-page introductory essay placing the book in historical and literary context.

But my experience has been more than an intellectual exercise; the memoir left me personally touched and enriched.

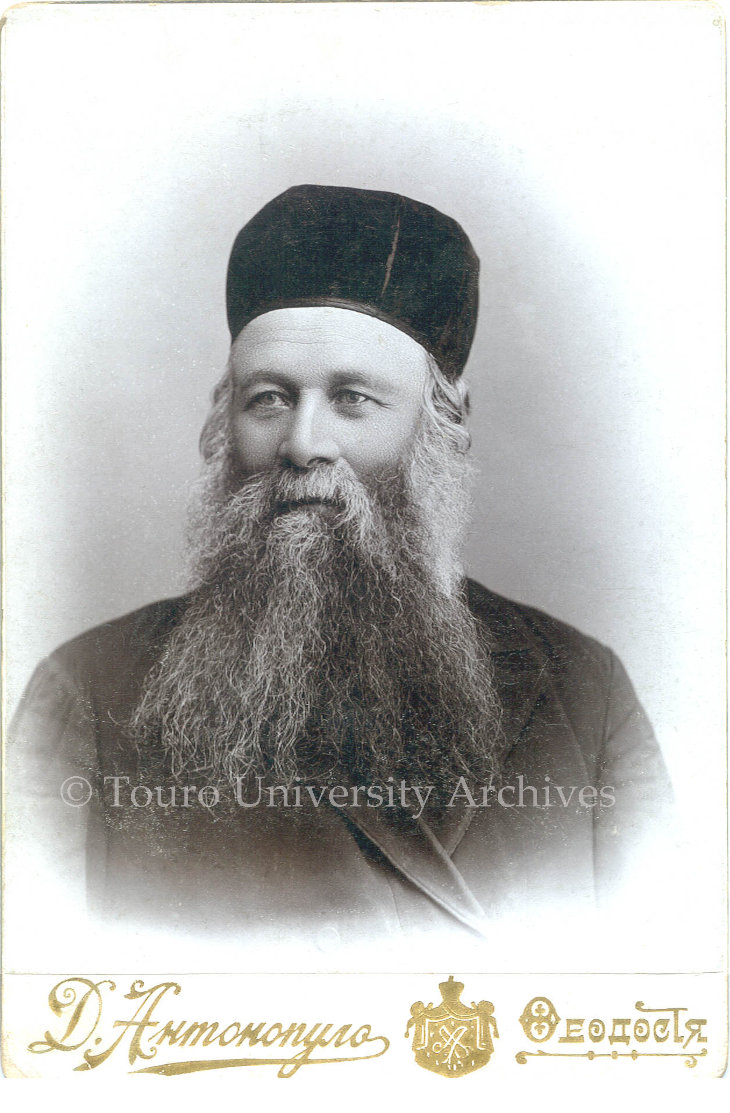

Pinye-Ber and his son Shloyme shortly before he left the Crimea for Petach Tikva.

Pinye-Ber and his son Shloyme shortly before he left the Crimea for Petach Tikva.

Here are four things that inspired me:

In Imperial Russia, which included Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania and Belarus, the Jewish subjects were targeted by thousands of antisemitic laws which restricted and penalized them at every turn. They groaned under the burden of crushing taxes and fines, and were told where they could live and which occupations they could pursue. And yet, despite this severe repression, the Jewish spirit remained remarkably high.

In one incident he recounts passing a nobleman who threatened to whip him for not doffing his hat to him. Goldenshteyn warned him not to do so, but when he did so anyway, Goldenshteyn grabbed him from behind. Each time the attacker tried to get away and assault him again, Goldenshteyn rammed his walking stick into his back.

For this, Goldenshteyn could well have been sent to a Siberian prison camp but he decided to stand up for what was right, no matter the consequences. The very next day, the news spread that the nobleman had shot himself out of embarrassment for having been bested by a Jew.

The draconian anti-Jewish laws in Imperial Russia caused a level of grinding poverty among the Jews in Imperial Russia far more severe than what existed among non-Jews. Goldenshteyn describes how his family often had to choose whether to buy food to eat or firewood to heat their home. Yet the deep-bred trust in God which even simple Jews of those times possessed gave them the emotional wherewithal to withstand the oppression and hardship they experienced.

When he was newly married, Goldenshteyn could not find work and wandered from village to village, lacking even minimal money to buy food. Yet he exerted himself to the utmost to be happy and would sing joyously, leading others to see him as the happiest person they’d ever met. Goldenshteyn knew that, as he put it, “Only by exerting myself to be joyous was I able to cast away the horrible worry from my heart.” Fortified by his unshakable faith, his search for a livelihood was ultimately successful.

The sages of the Talmud regard compassion as one of three distinguishing hallmarks of the Jewish nation, and I was struck by the lengths to which the author went in displaying that attribute. When Pinye-Ber became engaged, his prospective in-laws were well-off and they had promised to support the young couple, thereby enabling him to fulfill his dream of studying Torah without any financial worries.

The Shochet

The Shochet

But after he went off to study in a yeshiva following his engagement, his in-laws lost all their wealth. Upon hearing of this, Pinye-Ber could have broken off the engagement; in fact, other matches from wealthy families were suggested to him now that he was more learned. But the groom was concerned that if he broke the engagement, his fiancée Freyde might never be able to marry since at that time, a young lady without a dowry had few prospects of marrying. After much internal deliberation, his compassion prevailed and the two were married. Thus began a beautiful relationship in which husband and wife were truly devoted to each other.

A central Jewish belief is that everything that happens in the world is based on Divine Providence, and nothing occurs by mere happenstance or accident.

Pinye-Ber Goldenshteyn’s primary motivation in committing his life story to writing was to convey to his children, some of whom had strayed from Jewish observance, the instances of Divine Providence he had experienced in his life as a palpable demonstration of God’s existence.

For example, he tells of the many times he was spared from death and injury in situations of grave danger. In one such instance, upon moving to the Land of Israel, he was caught in the crossfire between Ottoman Turk and British forces during World War I. While engaged in writing a Torah scroll, he took a momentary break, and in that instant a cannonball fell on the exact spot where he had been sitting, leading him to observe: “God not only saved me then, but divine providence saved me constantly. Bombs landed near me many times, but I was not injured.”

The life lessons we learn from Pinye Ber are still powerful and relevant. I feel fortunate to have translated this book into English so that what he primarily intended as a legacy for his own family can now be a springboard of growth and inspiration for Jews everywhere.

It has certainly been that for me.

Wow, thank you for sharing this!

I read the first volume and greatly enjoyed it, recommended it to many people, and bought another copy for a relative!

Here's a moral question that's been bothering me about this memoir: The protagonist has a lot of commentary about a lot of people. How do the laws of forbidden speech (Lashon Horah) apply in terms of reading/believing his opinions?

I can’t wait to read this book. Thank you!