Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

5 min read

4 min read

3 min read

8 min read

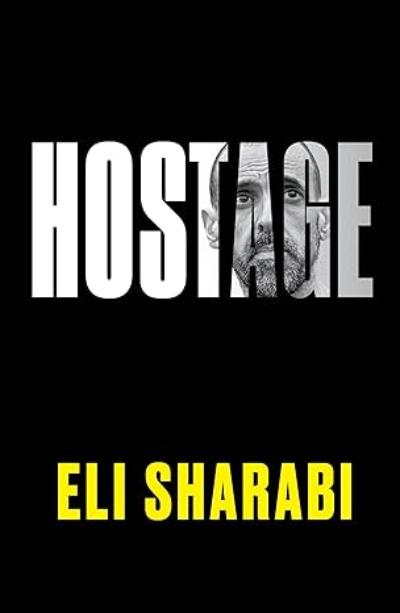

How his blockbuster book changed my life—and can change yours.

Eli Sharabi’s book Hostage, his account of the 491 days he spent as a captive of Hamas in Gaza, is the fastest selling book in Israel’s history. While Eli refers to himself as a non-religious Jew, his actions while in the depths of hell are snapshots of the essence of Judaism. Such mental images of true nobility, generosity, and responsibility, pulled out whenever we are feeling discouraged, depleted, or despondent, can ameliorate the much-touted despair of our anti-hero age.

Eli was kidnapped from his home in Kibbutz Be’eri on October 7. He would not find out until he was freed almost a year and a half later that his wife and two daughters were murdered on that day.

Taken through mobs of Gazan civilians who frantically tried to lynch him, Eli is eventually imprisoned in a family’s home in the upper floor of a building. His legs shackled and his arms tied tightly behind him with a rope that cuts into his flesh, he is subjected to repeated humiliations. Another hostage is with him, a Thai man named Khun who was an agricultural worker on the kibbutz. Despite his own trauma and physical pain, Eli takes on a mission: to help Khun. He writes:

Taken through mobs of Gazan civilians who frantically tried to lynch him, Eli is eventually imprisoned in a family’s home in the upper floor of a building. His legs shackled and his arms tied tightly behind him with a rope that cuts into his flesh, he is subjected to repeated humiliations. Another hostage is with him, a Thai man named Khun who was an agricultural worker on the kibbutz. Despite his own trauma and physical pain, Eli takes on a mission: to help Khun. He writes:

Khun is really struggling. There are times he cries a lot, bangs his head against the wall, loses control. Unlike me, he can’t get his head around the situation. The language gap, the cultural divide—everything is much harder for him. I try to protect him, as much as I can, to cheer him up. From the start, I understand I have a role with Khun, and I embrace it: to mediate the situation for him, to give him strength.

This sense of mission, to improve the situation, to “love the stranger,” as the Torah puts it, is quintessentially Jewish. The Torah not only commands acts of kindness, such as giving charity, but also enjoins us to be proactive when someone is suffering. “You shall not stand idly by while your neighbor’s blood is shed” (Leviticus 19:16).

A snapshot: Eli Sharabi, in physical pain and psychological trauma, instead of focusing on himself, undertakes to help an erstwhile stranger.

Since reading Hostage, when I am too tired or self-absorbed to bother to help someone else, I pull out the image of Eli taking on the mission to help Khun.

After 50 days in the apartment, the Hamas terrorists tell Eli that he is being moved. Escorted by an armed terrorist whom he has nicknamed, “the Cleaner,” he is taken to a nearby mosque. Eli tenses. Why a mosque? Why not another house?

In a side room of the mosque, Eli’s captor opens a trapdoor. Beneath it is a shaft leading into a dark tunnel. Eli trembles. “I clutch myself and shake my head: No. No, no. Not a tunnel … Please, just not a tunnel.” Eli is gripped by fear, but not by helplessness.

I look at the Cleaner. “I’m not going down.”

“It’s for your own good,” the Cleaner replies.

“I’m not going.”

“You’re going down!”

“I’m not.”

The Cleaner gives me a threatening stare. “Go down, right now,” he growls. I look at him. I have a choice. To go into the tunnel . . . or die. There is always a choice. Always a choice. There. Is. Always. A. Choice. I can choose to end my life here and now. Resist until the Cleaner shoots me and I fall bleeding on the mosque floor. I can choose that. Just like I could have chosen to resist in my bomb shelter at home until they shot and killed me. Some made that choice. It is a choice. Even when you have no control over yourself, you always have a choice. I look at the Cleaner, and I choose: I’m going down.

“There. Is. Always. A. Choice.” This is the essence of Judaism. While social scientists proclaim that everything is determined by heredity and environment, while professors teach the philosophy of victimhood, and while social Darwinists assert that human beings are merely animals, inexorably driven by instinct and natural drives, Judaism has always taught that humans beings are divine souls who have free will in the moral sphere. As the Torah commands: “I have set before you today life and good, death and evil … Choose life” (Deut. 30:15).

Eli with his wife and daughters

Eli with his wife and daughters

A snapshot: Eli Sharabi, a prisoner in the hands of brutal terrorists, standing at the entrance of a shaft leading to a dark Gazan tunnel, affirming to himself that he has a choice.

Since reading Hostage, whenever I feel compelled by circumstances or other people to act in a certain way, I pull out the image of Eli Sharabi standing at the entrance shaft to a Hamas tunnel and remember that I have a choice. “There. Is. Always. A. Choice.”

In the tunnel, Eli, 51 years old, is joined by three younger hostages: Elia, Or, and Alon. They are starved, given a single meal a day consisting of one and half stale pitas. They are routinely humiliated. They sometimes have to beg to use the bathroom. They are allowed to wash themselves from a bucket of cold water once every six weeks. Once, Eli is beaten senseless, his ribs broken, by a brutal Hamas terrorist.

Again, Eli takes upon himself a mission: to give emotional support to the younger hostages. He reflects:

I’m a father, so I’ve been practicing the art of self-sacrifice and living with people who need me for years… For better or worse, I have a role to play here. They need me to manage this situation. To take responsibility not just for myself, but for them. The others are also part of my mission of survival. Each needs something different from me.

He prevails on each of them to tell him, “something beautiful from your life,” leading them to precious memories of family and travels.

Every morning they start the day with the Jewish morning prayers. They stand up, their feet in iron shackles, and Elia, who was raised religious, recites the prayers by heart. The other three answer, “Amen.” On Shabbat night, lacking wine or grape juice, they make Kiddush over a cup of water. They make “Hamotzi” over a scrap of pita they have hidden away for Shabbat. When Shabbat ends on Saturday night, although they have neither the requisite Havdalah candle, wine, or spices, they recite Havdalah.

I don’t know if I feel God in those moments. But I feel power. I feel a connection. To my people. To our tradition. To my identity. It connects me to my family. To my childhood. To my roots. I reminds me why I must survive. Who I’m surviving for. What I’m surviving for.

Rootedness. The burgeoning phenomenon of “October 8 Jews,” Jews in the Diaspora who discovered through the Hamas attack who they are and who they want to be. Some Jews post-October 7 allowed the rising antisemitism to distance them from identifying with the threatened and hated Jewish community. For others, however, their tenuous connection to the Jewish People became stronger as they sought out rituals of Judaism and Jewish community connections they had previously ignored.

A snapshot: Eli Sharabi, a professed “non-religious” Jew, making kiddush on water in the tunnels of Gaza because that’s how he connects to his identity as a Jew.

One evening, Eli spontaneously comes up with an idea “to lift everyone’s spirits.” He encourages his fellow captives to think of something good that happened that day, and to share it.

At first, we rack our brains to think of one good thing. Then, as time goes by, we challenge ourselves to come up with three. Sometimes it’s really hard, and sometimes it’s easy to find three and we even continue to four or five… For example, if they suddenly let us drink tea. Or if the tea was sweet. Another good thing might be if a particularly cruel guard we dislike doesn’t show up that day. Or if the day went by without any humiliations. Or if we got a small piece of fruit from one of our captors. Slowly, this routine begins to affect our whole day. We find ourselves searching for the good things for which we can express gratitude in the evening.”

The Hebrew word for “Jew” is “Yehudi,” from the root word meaning to thank. Gratitude is a mainstay of Judaism. As the thrice-daily Amida prayer states: “We thank You for our lives, which are committed to Your power and for our souls that are entrusted to You; for Your miracles that are with us every day; and for Your wonders and favors in every season—evening, morning and afternoon.”

A snapshot: At the end of a difficult day, when I have trouble thinking of something to thank God for, I pull out the image of Eli Sharabi in the tunnels of Gaza, being grateful for a cup of tea or a bit of fruit.

Previous centuries read biographies of saints to inspire them. My 21st century version of hagiography is an ordinary Jew in the hell of Hamas tunnels exhibiting the extraordinary potencies of a Jewish soul.

Featured image by Blake Ezra. Visit his website at https://www.blakeezraphotography.com/

Beautifully written . Thank you for these important moments of thought.

Thank you for publicizing this book and Eli's story. Anyone who reads "Hostage" -- or even this short beautifully written article that highlights Eli's contributions to the collective soul of the Jewish people -- will surely be impacted for life.

Sara, I loved what you wrote SO MUCH. Thank you. Eli is a holy man, and I MOST loved that you called his book a hagiography.

I would skip the HOLD and buy a used copy. This is a “keeper!” Consider a modern day bible—not that it’s holy, but until you read it you have no idea of what our people went through. It’s a part of history that none of us should ever forget. Eli is a grand teacher. telling us of what is important in our lives. what we stand for….how noble people should comprehend, act and behave.

One of the best biographies that you’ll ever read and want to share with others. Eli indeed was a champion of the world!

I have a hold on this book at my library. The waiting list is long but it's worth it!

Heart breaking yet so amazing a very righteous man

Very inspiring. I’m definitely going to g to buy the book!

WONDERFUL!

It is refreshing to read articulated by another, my own belief: It is all about choice, always choice.

Touching indeed.

Thank you to Sara Yocheved Rigler for sharing this crucial story.

There are no words.

After reading Sara Rigler's superb commentary on Eli Sharabi's book, I'll immediately try to buy this book. I am already grateful to Eli for his strength and generosity in writing about his incredible experiences as a hostage of the cruel terrorists. And this after discovering the impossibly tragic fact that his wife and both daughters were not waiting at home but were murdered. This man is a deeply spiritual person whatever he calls himself. As Sara points out so clearly, he thinks and acts as a religious person needs to do, one who acknowledges that what happens to us is never random but minutely directed by the King of all Kings. Thank you, thank you. ChayaLeah

I felt the same way about this book - moving and enlightening particularly in terms of showing us what a Jew is made of - look beneath the surface - we don't really know who anyone is and what they are capable of. Religious, not religious...in the tunnels the pintele yid was revealed.