Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

12 min read

A new book tells the untold history of how Jewish immigrants transformed American whiskey.

A new book makes a provocative claim: the “world’s greatest spirit” owes much of its rise to an unexpected group of pioneers—Jewish whiskey merchants. In The Whiskey Bible (2025), Noah Rothbaum traces the drink’s sweeping history and reveals a surprising thread running through it: Jewish immigrants helped build America’s whiskey boom.

As Rothbaum puts it, “The influx of Jewish immigrants to the United States in the 1800s completely…revolutionized the liquor industry.”

Here are ten little-known facts about Jews and whiskey which Rothbaum uncovers.

During Colonial times, rum – not whiskey – was seen as the quintessential American alcoholic drink. In 1750, Massachusetts was home to 63 rum distilleries; the city of Newport, Rhode Island, was home to 30 rum distilleries. Yet with independence, the US quickly lost its access to British-grown sugar cane from the Caribbean. Molasses, a byproduct of sugar refining, is a key ingredient in rum.

Newly independent Americans turned to distilling other types of alcohol. Whiskey was a popular choice and was soon seen as a patriotic “American” drink. George Washington even forced his large workforce of enslaved people to produce thousands of gallons of whiskey each year on his plantation in Mount Vernon, Virginia.

Jews were key participants in this new industry. Whiskey distillers soon clustered among a handful of American cities: Peoria, Illinois, Chicago, and Cincinnati, though no city was more identified with American whiskey than Louisville, Kentucky. In the 1800s, Jews produced about a quarter of the city’s whiskey, even though Louisville’s population was only 3% Jewish. Jewish-owned whiskey producers shied away from lending their own names to their products. They adopted instead Anglo-sounding names which sounded more thoroughly “American.”

Jews were key participants in this new industry. Whiskey distillers soon clustered among a handful of American cities: Peoria, Illinois, Chicago, and Cincinnati, though no city was more identified with American whiskey than Louisville, Kentucky. In the 1800s, Jews produced about a quarter of the city’s whiskey, even though Louisville’s population was only 3% Jewish. Jewish-owned whiskey producers shied away from lending their own names to their products. They adopted instead Anglo-sounding names which sounded more thoroughly “American.”

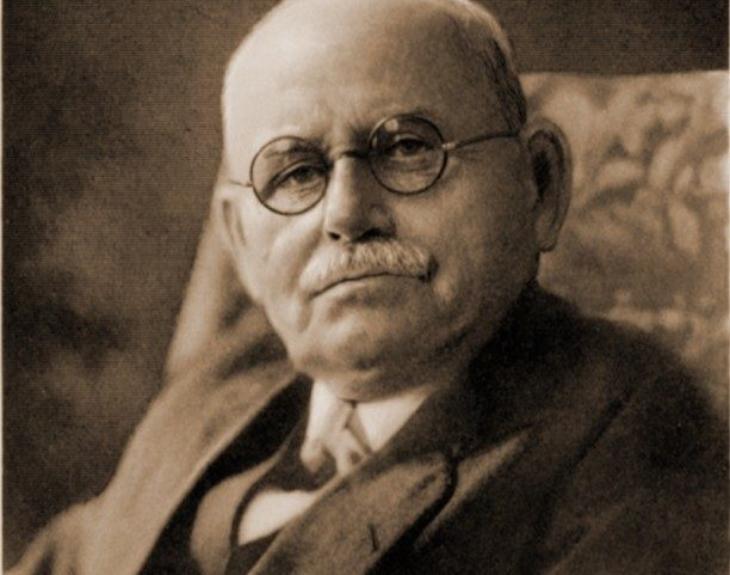

One of the largest whiskey companies in 19th-century America was built by Isaac Wolfe Bernheim, a Jewish immigrant who didn’t even particularly like whiskey. Concealing both his Jewishness and his personal tastes, he fashioned himself into an all-American whiskey king.

Bernheim grew up in a Jewish home in Germany and sailed to New York at age 18, just after the Civil War. He was so poor he couldn’t afford the plate and silverware that steerage passengers were expected to bring for themselves. Kindhearted workers in the ship’s kitchen slipped cooked potatoes into his hat, and he ate them on deck with his fingers.

Isaac Wolfe Bernheim

Isaac Wolfe Bernheim

The job he expected in New York fell through, so he found work as a peddler in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, trudging the streets with a sack of goods slung over his shoulder. He finally saved enough to buy a wagon and horse. After the horse dropped dead during his rounds, Bernheim moved on to Paducah, Kentucky—then a center of the burgeoning American whiskey industry.

There he met two fellow Jews, Moses Bloom and Reuben Loeb, and became a bookkeeper in their firm, Loeb, Bloom & Co. Bernheim took to the whiskey business quickly and prospered. He brought over his brother Bernard from Germany, and before long the two struck out on their own, founding Bernheim Bros., a company that soon dominated the whiskey trade.

From the start, Bernheim Bros. thrived. The brothers eventually purchased nine acres of scrubland outside Louisville and built a massive whiskey refinery complete with its own mill capable of turning out 2,000 bushels of rye a day, its own power plant, and seven warehouses holding 100,000 barrels of whiskey. Their best-known label was I.W. Harper—“I.W.” for Isaac’s initials, and “Harper” because it sounded Christian and obscured his Jewish origins.

Isaac and Bernard sold Bernheim Bros. to the United American Company in 1911. (I.W. Harper continues to be produced today and is owned by the liquor giant Diageo.) Isaac died in 1945, leaving his entire fortune to establish the Bernheim Forest and Research Center outside Louisville—a beautiful park and scientific center that still flourishes today.

Americans who supported Prohibition—banning the sale and consumption of alcohol with only limited exceptions—campaigned tirelessly throughout the 1910s. Many were driven by fears of rampant drinking; others were fueled by hostility toward Jews.

In the early 1900s, the American liquor industry was so heavily dominated by Jewish entrepreneurs that some prominent antisemites, including industrialist Henry Ford, embraced Prohibition in part to damage Jewish business interests.

In 1919, Congress approved the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the sale and ownership of alcoholic beverages. It passed with overwhelming support and remained the law for the next fourteen years, until its repeal in 1933. Even after Prohibition ended, strict regulations continued to govern the production of alcoholic drinks. Although Ford and other antisemites may have supported Prohibition out of enmity toward Jews, the damage they inflicted was short-lived. After 1933, Jews once again became major contributors to America’s whiskey industry—and to the broader world of alcoholic beverages—on an even larger scale than before.

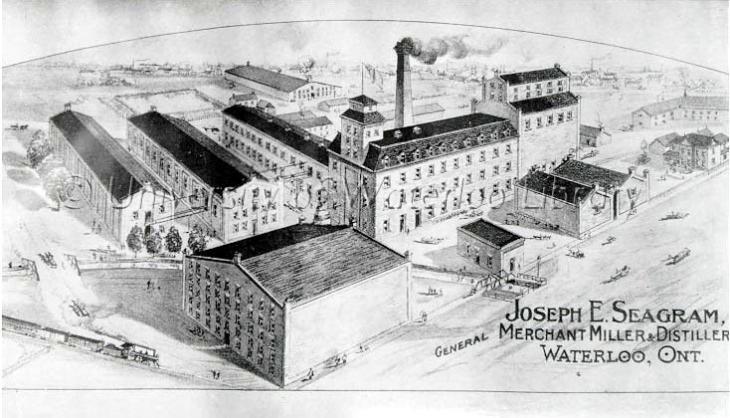

With the end of Prohibition, whiskey production ramped up again. Four giants emerged in the industry: Seagram, which was based in Canada and never had to cease operations; and US companies Hiram Walker, National Distillers, and Schenley. Seagram and Schenley were founded and led by Jewish entrepreneurs.

The Bronfman family’s vast whiskey empire began in Montreal, where Jewish immigrants Yechiel and Mindel Bronfman settled in 1899 after fleeing pogroms in Europe. They worked tirelessly in their new home, eventually buying a hotel, then expanding into additional hotels, bars, and finally the business of producing and distributing whiskey. (The name Bronfman means “whiskey distiller” in German, suggesting the family may have had roots in the trade back in Europe.)

Sam Bronfman (Excerpted from The Whiskey Bible by Noah Rothbaum (Workman Publishing). Copyright © 2025. Photograph by Crown Royal)

Sam Bronfman (Excerpted from The Whiskey Bible by Noah Rothbaum (Workman Publishing). Copyright © 2025. Photograph by Crown Royal)

As Jews, the Bronfmans faced persistent antisemitism. After purchasing the Joseph E. Seagram & Sons company in 1928, they rebranded their entire business empire as “Seagram,” a non-Jewish-sounding name chosen to counter the persistent anti-Jewish prejudice they encountered among customers.

When Prohibition took effect in the United States in 1919, the Bronfmans—along with many Canadian whiskey producers—found a way to sidestep the ban on exporting alcohol to the U.S. Canadian companies shipped millions of bottles to warehouses on two tiny islands just off the Canadian coast: Saint-Pierre and Miquelon. Though geographically adjacent to Canada, the islands were owned by France, making exports to them legal. From there, a network of bootleggers bought the whiskey and smuggled it into the U.S.

Seagram’s ad from 1935

Seagram’s ad from 1935

This maneuver kept Seagram afloat. After Prohibition ended in 1933, the Bronfmans invested millions in the American market, building new distilleries and acquiring smaller brands. Within a few years, they had become one of the “big four” whiskey companies in the United States. As their empire grew, so did their philanthropy.

Schenley was another of the “big four” whiskey companies that dominated the American market in the mid-20th century. It was built by Jewish whiskey producer Lewis Rosenstiel, who shaped the industry in countless ways, including helping establish the practice of aging American whiskey for 20 years or more—mirroring the traditions long used by distillers in Scotland and Ireland.

Rosenstiel made two bold gambles that first turned him into a major player and then transformed American whiskey itself.

As a young man, he worked at his uncle’s whiskey company in Milton, Kentucky, before striking out on his own. In the mid-1920s, confident that Prohibition would soon end, Rosenstiel positioned himself to be ready the moment it did. In 1925, he purchased a small Pennsylvania distillery named Schenley, one of the very few operations holding a “medical whiskey” license during Prohibition. This allowed it to continue functioning—albeit modestly—while most of the industry shut down. When Prohibition ended in 1933, Rosenstiel’s company expanded rapidly and became one of the largest whiskey producers in the United States.

Lewis Rosenstiel

Lewis Rosenstiel

During World War II, many distilleries were requisitioned by the U.S. government to produce high-grade alcohol for weapons and fuel. As tensions with the Soviet Union escalated, Rosenstiel became convinced the nations would go to war and that whiskey production would again be halted. He began stockpiling whiskey in anticipation.

War never came, and Rosenstiel was left holding a massive surplus. At the time, American whiskey was considered mature—and taxed accordingly—after eight years of aging. As his reserves approached that threshold, he faced a ruinous tax bill. Rosenstiel began lobbying the government to change the standard, arguing that the great distillers of the British Isles routinely aged fine whiskies for 20 years or more. Thanks to his efforts, the United States eventually adopted 20 years as the benchmark for whiskey maturity—and as the basis for taxation.

Lewis Rosenstiel also helped ensure that bourbon—a distinctly American style of whiskey—was protected and recognized as a vital part of American culture.

Since colonial times, American distillers had produced whiskey, though its composition varied widely by region. Whiskey is distilled from fermented grains, often a blend of rye, wheat, oats, and barley. In the American South, distillers began incorporating corn, which lent the spirit a sweeter flavor. By the 1800s, southern distillers were calling this variation bourbon, possibly after Bourbon County, Kentucky. Bourbon is aged in charred oak barrels and develops deeper, more complex flavors the longer it rests in its casks.

In the 1960s, Rosenstiel lobbied vigorously to have bourbon recognized as a unique cultural product with a protected designation. Just as tequila can only be produced in Mexico and champagne only in France, Rosenstiel believed bourbon should be tied to a specific place and process. He founded the Bourbon Institute in 1958 to advocate for nationwide standards defining what made bourbon bourbon, and to ensure that anything labeled as such was produced exclusively in the United States.

In 1964, he succeeded: Congress formally codified the requirements for bourbon and declared it an American-specific spirit. Bourbon was defined as a U.S.-made whiskey with a mash bill of at least 51% corn, distilled at under 160 proof, and aged in new, charred oak barrels.

The “big four” whiskey companies that rose to dominance after Prohibition have long since been absorbed by massive multinational corporations. A few smaller distilleries, however, remain in family hands. Most notable among them is Heaven Hill, founded by a Jewish immigrant named Max Shapira.

Born in Lithuania, Max immigrated to America in the 1910s. He first tried his luck in New Orleans before moving to rural Kentucky, where he worked as a peddler. His five sons eventually opened a chain of stores across Kentucky. In 1935, in the wake of Prohibition’s repeal, the brothers secured a few investors and made a down payment on a parcel of vacant land near Bardstown, Kentucky. They named the venture Heaven Hill—a positive, non-Jewish-sounding name adapted from that of the farmer who sold them the land, Mr. Heavenhill.

The Shapira brothers built a distillery, warehouses, and packaging facilities, and soon began producing high-quality bourbon. Today, Heaven Hill remains in Shapira family hands and is the largest independent, family-owned whiskey distillery in the United States. They produce some of America’s most beloved whiskeys, including Evan Williams, Elijah Craig, Rittenhouse Rye, and Old Fitzgerald.

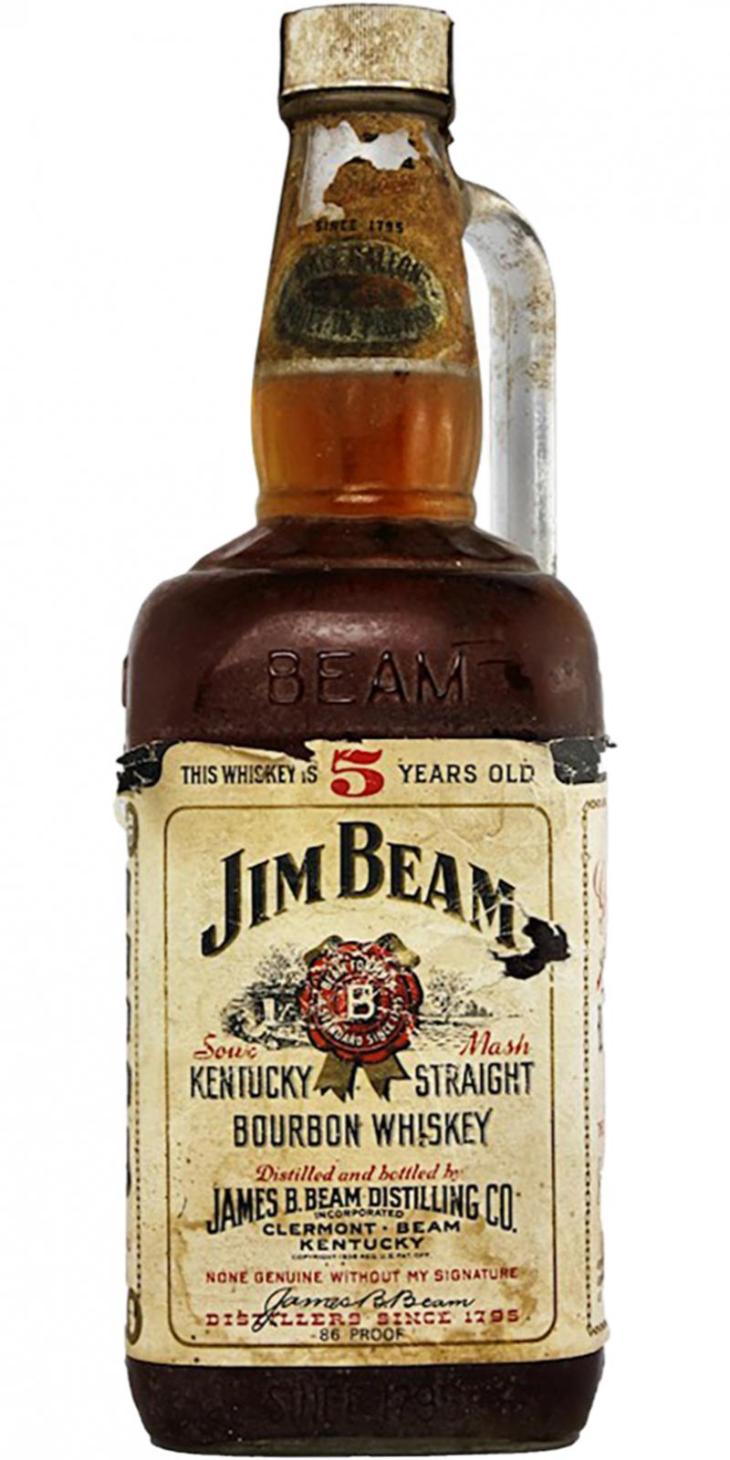

Perhaps the most iconic name in American whiskey is Jim Beam. The company was founded in 1795 by Jacob and Johannes Beam, who produced and sold corn-based whiskey in Pennsylvania. It remained in the Beam family into the Prohibition era, when it was led by James Beauregard Beam. In 1919, a mob stormed the main Jim Beam distillery and destroyed all of its equipment, leaving James financially devastated.

During Prohibition, he survived by quarrying rock. When the ban on alcohol finally ended, James was determined to rebuild the family brand—but he had no capital. He turned to a group of Jewish investors in the heavily Jewish Chicago suburb of Deerfield, Illinois. They quietly purchased Jim Beam and assumed responsibility for the company’s sales and marketing, while James Beauregard Beam continued to oversee the distilling of the family’s signature whiskeys.

During Prohibition, he survived by quarrying rock. When the ban on alcohol finally ended, James was determined to rebuild the family brand—but he had no capital. He turned to a group of Jewish investors in the heavily Jewish Chicago suburb of Deerfield, Illinois. They quietly purchased Jim Beam and assumed responsibility for the company’s sales and marketing, while James Beauregard Beam continued to oversee the distilling of the family’s signature whiskeys.

Today, Jim Beam is owned by a Japanese conglomerate, and few realize that it survived Prohibition and the Depression only because a group of Jewish owners helped keep the brand alive.

Today, craft whiskey – small, independently made whiskeys with unique characteristics – are all the rage. In 2021, there were over 2,290 craft distillers in the United States. Many of these new whiskies are being developed by Jewish whiskey-makers. One of these is Koval, a craft distillery in Chicago, which was founded in 2008 by Dr. Sonat Birnecker-Hart, a Shabbat-observant former tenured professor of Jewish studies. Koval produces a range of kosher spirits, including bourbon and whiskey, part of a trend of new and unusual whiskies - often with Jewish distillers leading the way.

Author Noah Rothbaum (photo: Eric Medsker)

Author Noah Rothbaum (photo: Eric Medsker)

Author Noah Rothbaum notes that in addition to the central role Jews have played in the American whiskey industry, today “There’s also a new generation of Jewish distillers running craft distilleries across America.”

Note:

This article highlights the rich and often overlooked Jewish history behind the development of American whiskey. It should not, however, be understood as implying that the whiskeys mentioned are kosher. Questions of kashrut depend on specific production processes and certification, and many of the brands discussed here are not certified kosher.

You can purchase Jim Beam in any grocery store here in Israel.

Good article discussing the Jewish roots of the North American whiskey trade. Lots of kosher brands out there, including one by The Bourbon Rabbi in the Louisville, KY, area. Today, a lot of the bigger bourbon/American whiskey conglomerates are owned by yiddin. [BTW, one of the main reasons a lot of bourbons are not kosher is the failure to sell chametz during Pesach, which I understand is something being worked on in the Louisville, KY, area]

Excellent article, and as a Jew and a Bourbon drinker (other whiskeys and Scotch too, for the record), I can "identify!" CHEERS!!!