Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

12 min read

A short, practical guide explaining the unique stages of a traditional Friday night meal, including deeper insights into various customs.

The weekly Jewish Sabbath, called “Shabbat” (or Shabbos, depending on where you’re from), begins each Friday night at sundown, and then—following a private candle lighting service and evening prayers—you eat.

But a Friday night dinner isn’t just a meal—not that that’s a bad thing—it’s a festive occasion that often includes guests, extended family, special foods, songs, prayers, meaningful conversations and other significant customs.

How do you run a Friday night meal? What do the different practices and ceremonies mean? This primer will answer your questions and tell you what to do.

The Jewish day starts at sundown, which is derived from the way the Torah describes the creation of the world, “God named the light “Day,” and the darkness He named “Night,” and it was evening and it was morning, one day (Genesis 1:5).” “Evening” proceeds “morning,” implying that sundown, and not sunrise—or midnight, or some other point in a 24-hour cycle—marks the start of the Jewish day.1

That said, Friday night dinner—the first of three meals eaten on Shabbat, the other two being “the Shabbat day” meal that’s usually eaten around lunch time, and “Third Meal,” which is eaten in the late afternoon—is the inaugural Sabbath meal, and an opportunity to take note, and to acknowledge that you’re entering a different, and elevated, spiritual space.

Shabbat is the fourth of the Ten Commandments. It is listed after three commandments that describe and define your relationship with God, but before the commandments that delineate specific moral precepts. It’s listed that way in order to demonstrate the idea that God created the world for your benefit and pleasure, and that internalizing that idea starts with observing the Sabbath. It also precedes—and should inform—your moral behavior: life is a gift, use it to be a source of good.

The Shabbat dinner table is set before the meal begins—and usually earlier in the day, before the Sabbath candles are lit, and before heading off to synagogue services—and includes an array of items needed to run a successful meal. Some of the essentials include:

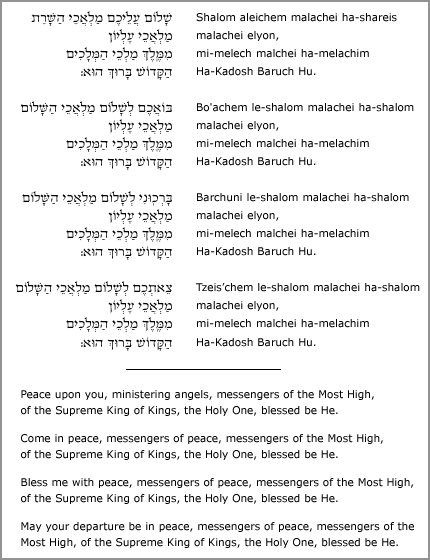

Friday night dinner starts with three customs that have nothing to do with eating, the first being the song, “Shalom Aleichem.”

Shalom Aleichem is a Hebrew idiom—it literally means, “peace unto you” (or technically, “y’all,” in that the “you” here is plural)—and is used as a way to say, “Welcome.” But who are you welcoming? It’s not your guests or family members returning from synagogue. Rather, it’s angels, which, to the uninitiated, might seem a little weird.

But angels in Jewish tradition, and not the winged creatures popularized in movies and fairytales, have deep spiritual roots. The Hebrew word for angel is "malach (מלאך)." That means "messenger," and can also mean "work." In Jewish thought, an angel is a "messenger" from God that carries out His "work." It's a metaphysical concept used to explain how God's will becomes manifest in the mundane, physical world.2

On Friday night, that messenger is an agent of peace, and singing the song, Shalom Aleichem, articulates your hope that God—in response to your preparation and observance of Shabbat—will enable peace to be manifest in your home.

Eishet Chayil, usually translated as “Woman of Valor,” is another song sung on Friday night, and is taken from the book of Proverbs (30:10-31). The song is considered a praise of numerous things including the Torah, the soul, and the Shabbat, although it’s most often understood as a praise of Jewish women.

On a deeper level, Eishet Chayil refers to the Divine Presence, or a feminine aspect of God. It evokes a side of divinity that’s less tangible, but felt on a deeper, more intuitive level; and speaks to the holiness that’s felt—although difficult to articulate—that is integral to experiencing Shabbat.

Blessing the Children. Shabbat is an essential link in a chain that extends back to the birth of the Jewish people, and its observance precedes the Ten Commandments and the national revelation at Mount Sinai.3 Jewish survival is predicated on transmitting Jewish laws and traditions from one generation to the next.

And that starts at home, with your family.

Blessing your children is a part of that process. It shows you understand the Jewish future is in your hands, a future that is renewed whenever your family embraces its Judaism together, particularly on Shabbat.

The Torah, in a number of different places, details various laws regarding Sabbath observance. One important commandment is found in Exodus, 20:8, which is to “remember” the Sabbath.

In Jewish law, remembering the Sabbath is understood as doing something that acknowledges the day’s beginning and ending with words, and saying something like, “Shabbat Shalom,” technically fulfills that requirement. However, the rabbis, going back to Talmudic times, instituted a formal declaration that’s said over a cup of wine.4 On Friday night, that declaration includes the verses from the book of Genesis that describe the first Shabbat (Genesis 2:1-3), as well as two blessings: one for wine, and another to sanctify the day.

Unlike other auspicious times throughout the year that fall on a specific date that’s marked on the calendar—and is therefore subject to different astronomical observations, calculations, approximations, and assumptions (go here to see an in-depth explanation for how the Jewish calendar is determined)—Shabbat happens every seven days, no matter what. On a mystical level, that means that Shabbat’s holiness is intrinsic—it doesn’t vary—and it occurs regardless of what mankind measures and observes. It also implies that nothing, no matter what, takes precedence over Shabbat.

Kiddush is the opportunity to note that at the outset. Over a cup of wine you declare that God runs the world. He created it for your pleasure and benefit, and you’re along for the ride.

This is the full text of Kiddush.

The bread eaten on Shabbat is called challah, although like most things Jewish, the way it’s made varies from place to place.

The origin of the name is from the Torah, and refers to a tithe that both homemakers and professional bakers took from the doughs they were kneading, and then designated for a higher, spiritual purpose (in ancient times, it was baked into loaves of bread and donated to the people who worked in the Temple in Jerusalem).

Nowadays, a small symbolic tithe is still taken (and burned), and the name—and therefore a memory of the idea—is kept alive via its association with the breads you eat on important occasions.

Challah is considered holy, and on a deep, mystical level represents humanity. When God made the world, He kneaded the dough of the earth, so to speak, and took a small tithe, which He then formed into man. With that, humanity was separated from the rest of creation, and given a higher purpose and meaning.

At each Shabbat meal, you make a blessing on two challahs, in commemoration of the miraculous double portion of bread, called manna, that is described in Exodus 16:29-30, “‘You must realize that God has given you the Sabbath, and that is why I gave you food for two days on Friday. [On the Sabbath] every person must remain in his designated place. One may not leave his home [to gather food] on Saturday.’ The people rested on Saturday. The family of Israel called the food manna.”

That abundance, similar to the double portion described in Exodus, is an important Shabbat theme: you refrain from work, but the world doesn’t stop. Not only that, but despite your lack of effort, your needs are still taken care of. Observing Shabbat—and that includes the Sabbath meals—is a testament to the belief that God, ultimately, is running the show.

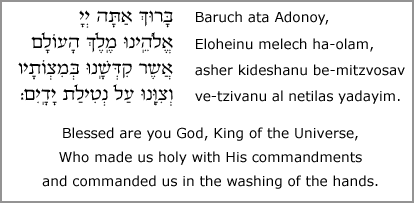

What to do? Go to the sink, take the special washing cup, pour water on each hand two or three times, make the blessing “Al Netilat Yadayim,” return to your seat, and sit quietly. When everyone has washed their hands, take the challah, make the blessing, “HaMotzi,” cut the bread, dip a piece in salt, and take a bite. After that, cut and distribute pieces to everyone else. At that point, it’s ok to talk.

Shabbat Zemirot are a collection of songs sung throughout the Shabbat meal. These songs enhance the spiritual flavor of your Shabbat meal, and they’re found in most Jewish prayer books, as well as in a special booklet that goes by various names like Bencher, Zemirot Shabbat (Sabbath Songbook), Birchonim, and more.

Some Shabbat songs are ancient, and were derived from poems written in the Middle Ages. The mystical schools based in Tzfat in the 16th century also composed many Shabbat Zemirot. Other Zemirot are even more recent. Zemirot are sung in many languages including Hebrew, Aramaic, Ladino, and Yiddish, although some communities only sing wordless melodies (called nigunim).

For many Zemirot, the words are fixed, but the melodies change over time, and, in addition to the new melodies that creative people come up with, you can also adapt the words to popular songs, or even make up your own. The point is to use the music to elevate your meal, but what that looks like is up to you, whether it’s serious and somber, playful and joyous, or raucous and wild. Let the spirit move you.

Go here for a collection of song options.

Every Shabbat meal ends with the Blessings After The Meal. These blessings, which consists of four main sections, as well as a series of additional blessings and requests, is one of the few blessings mentioned in the Torah itself (Deuteronomy 8:10): “When you eat and are satisfied, you must therefore bless God your Lord for the good land that He has given you.”

The point of each of the four blessings is to:

It’s not a Shabbat meal without food. In addition to challah and wine, most Shabbat meals include salads, fish, meat, an abundance of sides, and dessert. But what those food choices are are as varied as the Jewish people and range from excessive grease and starch to the staples of Mediterranean eating. Visit our Shabbat page on Jewlish for an almost endless list of options and ideas.

The most important thing to bring to a Shabbat dinner is a smile on your face and a positive attitude. If you’re invited to a Shabbat dinner and don’t want to show up empty handed, the best thing to bring is a bottle of wine. It’s easy, and always appreciated. Other common gifts include a bouquet of flowers, cakes or other desserts, booze, and the like.

A Shabbat dinner is a holiday feast and you should dress accordingly. Business casual is the general rule: sport coat and tie for men, and skirt and nice blouse for women, but ultimately, what you wear is up to you, and should reflect your good taste, personality, and style.

Guests should check with the hosts about appropriate dress. Business casual may be too casual in some homes, and overdressed in others. With heat indexes over 100 degrees (F) this summer, for example, a jacket and tie are not de rigeur everywhere.

But don’t show up in jeans and a t-shirt, nor mini skirt nor shorts. Neat, clean, and modest are always in style.

what about chulent????????????????????

That’s Shabbat lunch.

Excellent guide! Needs to be permanently indexed on Shabbat.com!