Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Jewish Geography

Jewish Geography

5 min read

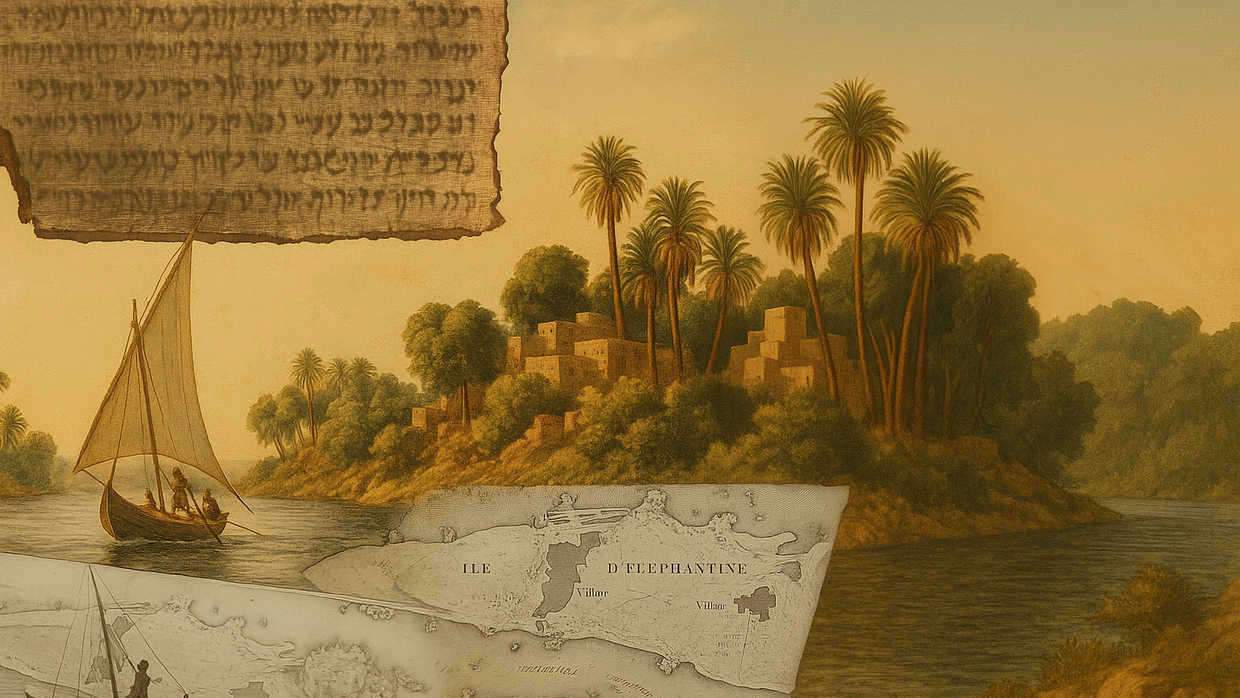

On a fortress in the middle of the Nile, an ancient Jewish community navigated the cross-currents of tradition and assimilation.

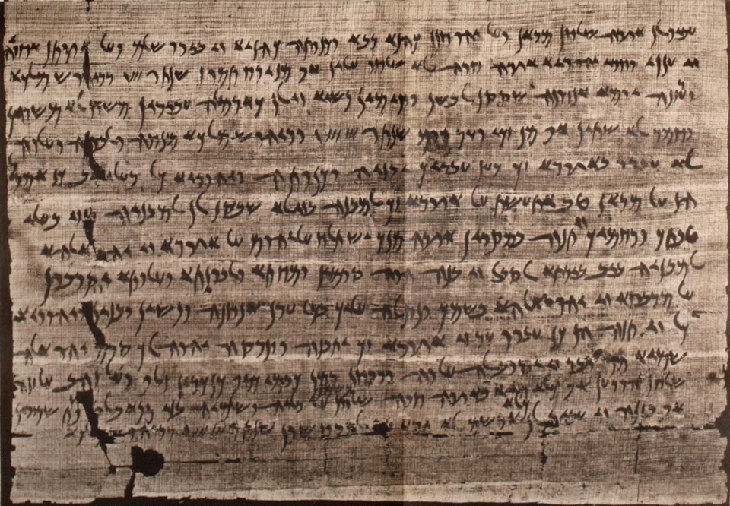

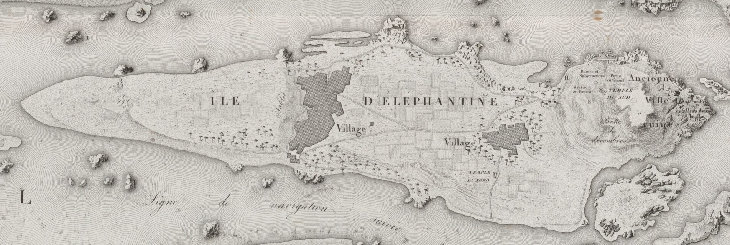

In the far south of ancient Egypt, just downstream from the first cataract of the Nile, lies a narrow strip of land called Elephantine Island. For centuries, it stood as a key military outpost in the Persian Empire, guarding against southern invaders from Nubia. Today it is mostly ruins. But hidden among the stone and dust, archaeologists uncovered a remarkable window into Jewish history—one of the only ancient Jewish communities whose voices we can still hear directly.

Beginning in the 6th or 5th century BCE, Jewish soldiers lived on Elephantine as part of the Persian military garrison. These Jewish soldiers and their families lived alongside local Egyptians and Persians. They built homes, raised families, conducted business, and practiced their ancestral religion.

How exactly this community began remains a mystery. But the deeper mystery is not how it began—but what it became.

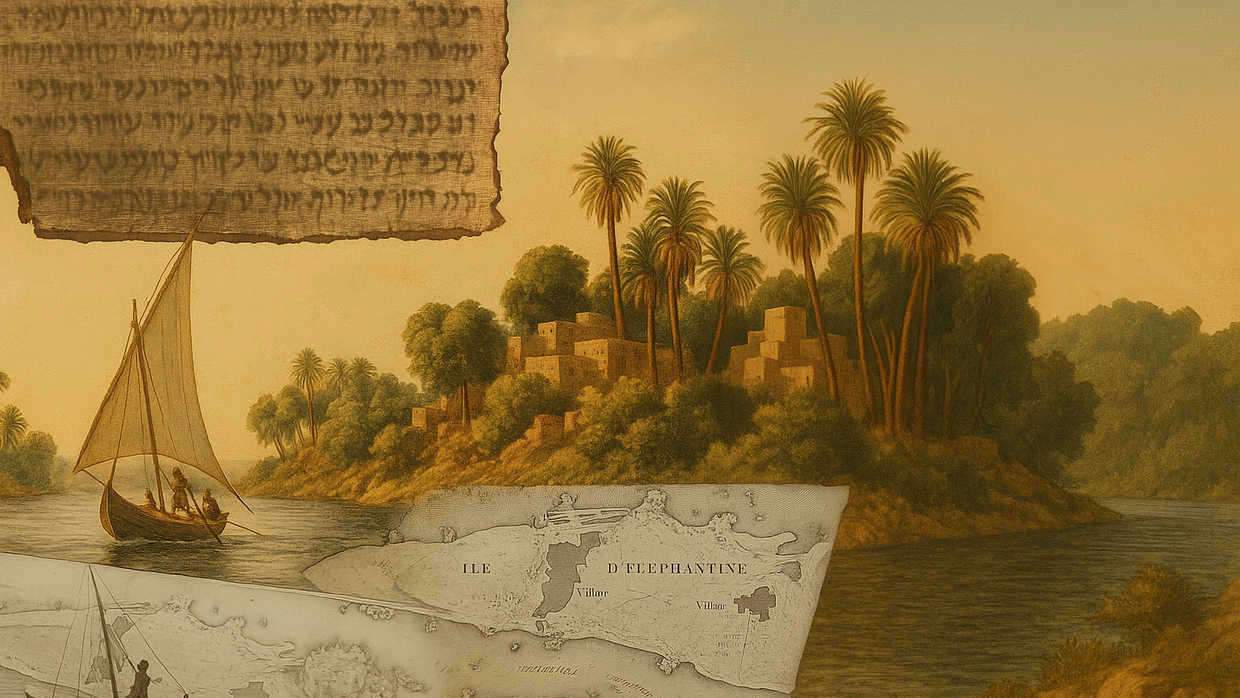

Among the many documents found on Elephantine, perhaps the most astonishing is a letter written by a Jewish priest named Yedoniah. In 408 BCE, he and his fellow community leaders wrote to a Persian official named Bagoas, the governor of Judea, as well as to the High Priest in Jerusalem.

Their request? Permission to rebuild their temple.

The papyrus requesting the rebuilding of their temple

The papyrus requesting the rebuilding of their temple

This was no mere synagogue. According to their own writings, Elephantine possessed a fully functioning temple service, with animal sacrifices, incense, and gold and silver utensils. It had recently been destroyed by priests of the nearby Egyptian temple, who may have been provoked by local political tensions. The Jews of Elephantine sought help from their distant brethren to restore it. Though Torah law clearly prohibits offering sacrifices outside the one designated sanctuary in Jerusalem, the Elephantine priests zealously maintained their own.

What makes this even more perplexing is that these Jews saw nothing inappropriate in what they were doing. Their appeal to the Jerusalem priesthood suggests they believed their temple would not be offensive to Jewish leadership. It seems they were unaware of the prohibition, and Yedoniah's letter conveys some surprise that the High Priest has been ghosting him. This has led many scholars to conclude that, while they identified strongly as Jews, Elephantine was largely ignorant of key elements of Jewish law.

Despite their confusion regarding Jewish law, the Jews of Elephantine clearly felt a deep connection to their heritage.

One of the most remarkable documents is a letter detailing how the community observed the holiday of Passover. It instructs the recipient to eat unleavened bread (matzah), to avoid fermented products, and to celebrate for seven days beginning on the 14th of Nisan—exactly as prescribed in the Torah.

The Elephantine Island

The Elephantine Island

Their Judaism may have diverged in some ways from that practiced in the Land of Israel, but it was not superficial. It was active, communal, and spiritual. In a pluralistic and polytheistic society, the Jews of Elephantine continued to serve the God of their ancestors—offering sacrifices, honoring holidays, and marking life-cycle events according to their understanding of tradition.

The papyri recovered from Elephantine don’t just record religious matters. Many are legal documents—contracts, receipts, and marriage agreements—that paint a vivid picture of daily life in this distant community. Among the most moving is the story of Ananiah, a Jewish temple official, and his wife Tamut, an Egyptian slave.

When Ananiah married Tamut, she had not yet been freed. Over time, their relationship—and her legal status—evolved. Many years into their marriage, Tamut and her daughter were formally emancipated, and the couple went on to purchase a large home just across the street from the Jewish temple.

They lived next to Egyptians and Persians. They made business deals, drafted wills, and arranged their daughter’s marriage. When Ananiah and Tamut passed away, their daughter inherited the house. Through these fragile fragments of papyrus, we glimpse the real humanity of their lives—their love, their challenges, and their desire to build a future for their family.

The Jews of Elephantine are not our spiritual ancestors in any traditional sense. Their temple was a strange and fascinating anomaly in Jewish history, and their practices diverged from what would later become rabbinic Judaism. And yet, they remind us of something profound and enduring.

For much of Jewish history, our people have lived at the intersection of tradition and assimilation. Sometimes, as in Elephantine, that tension has led to confusion and error. But just as often, it has led to creativity, resilience, and reinvention. The Jews of Elephantine lived centuries before the codifications of the Mishnah or the Talmud. They may not even have had a complete Torah scroll. But they knew they were Jews. They worshipped the God of Israel. They celebrated the Exodus from Egypt while living in Egypt. And they preserved that identity in a world that made it easy to forget.

Today, we are blessed with access to Torah, community, and learning on a scale they could not have imagined. But we still face the same underlying question: how do we live as Jews in a world of competing values and cultures?

The answer may lie not in the Elephantine temple, but in the yearning that built it—a desire to remain connected, to honor our past, and to build a Jewish life that speaks to the realities of the present.

Primary Source: Schiffman, Lawrence, ed. Texts and Traditions: A Source Reader for the Study of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism (Ktav Publishing House, 1998).

What about the temple south of Jerusalem in Adad, and at Mt. Gerzem, and Bethel and Dan.

My mother's maiden name is Elefant, from her father's side, a Jewish family from Poland before the War. I’ve always found it a unique name. Could it originate from Elephantine? Is that why the name was chosen? It seems common for surnames to derive from a family's place of origin.

One of my favorite chapters in Jewish history. Thanks Rabbi Campbell.

Such a thing as Judaism in North West London

I didn't.t know that such a thing as Elephantine existed!

Learned of it along time ago but now I know more . And there is a lot more to learn

don't they claim to have the ark of the covenant or is that a different group?

my mistake. That is in Ethiopia - Aksum

THERE WERE TWO TEMPLES in EGYPT!!! Leontopolis 160 BCE Tell el-Yahudiya, Nile Delta & Elephantine Elephantine Island, Aswan 5th c BCE

My understanding is that Elephantine was where the prophet Jeremiah took refuge when Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians. It was a community of both Judeans and Samarians.

It is incredible to think of the tremendously varied and long journey our people have taken to get to today! Humbling and beautiful! Not a story I could have imagined up and it is mind blowing to see His Authorship in history!

Are there books in English please about the Elephantine Jews?

Probably . It takes an online search.