Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Jewish Geography

Jewish Geography

10 min read

Journey to Djerba—an island where Judaism has flourished for 2,500 years, blending ancient Torah, vibrant tradition, and living faith in one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities.

Where did Jonah try to escape when he fled from God’s command?1 Where did King Solomon’s ships set sail to bring back ivory, monkeys, and peacocks?2 The Bible calls it Tarshish—a name wrapped in mystery and legend. Isaiah himself speaks of the mighty “ships of Tarshish.”3 But what if I told you that Tarshish may not just be a place in ancient text, but a land you can still walk upon today?

Jewish commentators across the centuries identified Tarshish with ancient Carthage4, the great North African power whose ruins still rest in modern-day Tunisia5. As a young yeshiva student first encountering the word Tarshish, I never imagined I would one day set foot there. Yet, about 15 years ago, I was blessed with the opportunity to travel as a scholar-in-residence with Miriam Schreiber’s Legacy Kosher Tours—and Tarshish became more than a word in the Bible. It became real.

This past summer, I once again set out for Tunisia and I discovered something different: not just another exotic destination, but perhaps the most inspiring Jewish experience I have had outside the Land of Israel. And at the heart of it all lay the jewel of Tunisia: the island of Djerba.

Mainland Tunisia itself is a wonder. Imagine walking through a fully intact Roman coliseum, wandering an ancient city frozen in time, or driving from the endless golden sands of the Sahara Desert to lush groves of olives and dates. Tunis, the capital, boasts an active synagogue built in elegant Art Deco style—still active and serving the local Jewish community of about 300 people— a Jewish school, and even a kosher butcher. Incredibly, there’s a synagogue at a beach resort that still holds three daily prayer services throughout the summer.

The highlight of our trip to Tunisia was Djerba. Djerba is an island of about 200 square miles and a population of 185,000. The Jewish community on Djerba is about 1,300 strong and is arguably the oldest, continuous Jewish community in the world outside Israel.

By Bellyglad from Tunisia - Synagogue at DjerbaUploaded by stegop, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20975035

By Bellyglad from Tunisia - Synagogue at DjerbaUploaded by stegop, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20975035

It is believed that the first Jews arrived in Djerba after the destruction of the First Temple about 2,500 years ago. Those who came were mostly Cohanim, descendants of Aaron the High Priest, who brought with them a stone from the altar in the Temple and embedded it in the foundation of the Al Ghriba synagogue.

Today the Jewish population of Djerba is mostly Cohanim, and the Al Ghriba synagogue, albeit not the original building, is still a place of pilgrimage and prayer for Jews around the world. In the first and second centuries BCE, Jews settled in Djerba when it was first Carthage and then under the rule of the Roman Empire. After the destruction of the second Temple in 70 CE, more Jews came to Djerba where the community flourished under the Romans although experiencing some pressure under Byzantium.

Following the Arab conquest of North Africa, Jews in Djerba were granted dhimmi status — a protected but subordinate position under Islamic rule that required the payment of, jizya, a special tax. The Jewish community thrived, enjoying a degree of autonomy that allowed for the preservation of its religious and cultural identity.

During the medieval period, Tunisia emerged as a significant center of Torah study and served as a vital conduit for the transmission of Torah teachings from the academies of Babylon to the shores of the Mediterranean. Historical records mention the presence of prominent scholars from the academies of Babylon and Italy residing in Tunisia.

A Jewish woman and children outside a synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia (Wiki commons)

A Jewish woman and children outside a synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia (Wiki commons)

A well-known legend tells of four leading Torah scholars who were captured by pirates while traveling across the Mediterranean. These scholars were later ransomed by Jewish communities in Cordoba (Spain), Narbonne (France), Alexandria (Egypt), and Kairouan (Tunisia), thereby dispersing their knowledge across these important centers of Jewish life.

One of the most remarkable artifacts from this era is a letter preserved in the Cairo Genizah, written by a Gaon (Torah Sage) of Kairouan to a relative in Egypt, dated to the 10th century CE. Kairouan itself was home to a renowned yeshiva headed by Rabbi Yitzhak al-Fasi. He later relocated to Spain, where he established another influential yeshiva in Lucena. Among his distinguished students were Rabbi Yehuda Halevi and his close friend Rabbi Yosef ibn Migash. The latter became the teacher of Maimon, whose son—Moshe—became known to the world as Maimonides

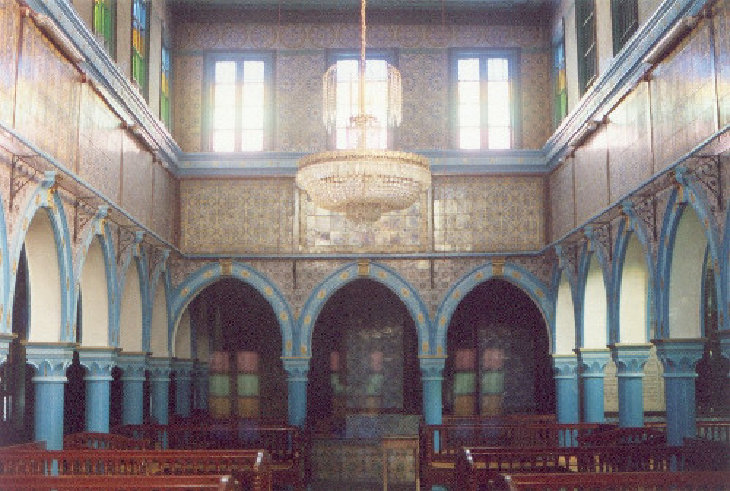

Inside the El Ghriba Synagogue By Chapultepec, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1930877

Inside the El Ghriba Synagogue By Chapultepec, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1930877

By the 11th and 12th centuries, Djerba had become a notable center of Jewish scholarship and Kabbalistic activity. At the heart of this intellectual and spiritual life was the El Ghriba Synagogue, which emerged as a cornerstone of religious practice and tradition, drawing pilgrims and scholars alike. In the 15th and 16th Centuries after the expulsions from Spain and Portugal many refugees came to Tunisia bringing their Andalusian heritage and culture to North Africa.

In 1574, Djerba and the wider Tunisian region came under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Under the millet system, which allowed religious minorities to manage their own communal affairs, the Jews of Djerba maintained a distinct cultural and religious identity. This period of relative isolation helped preserve ancient traditions, including the use of the Judeo-Arabic language and the meticulous maintenance of priestly (Cohen) lineage.

The onset of the Colonial Period in 1881, when Tunisia became a French protectorate, brought profound changes. The influence of French culture and modernity introduced new educational opportunities, notably through schools established by the Alliance Israélite Universelle. These changes prompted some members of the Jewish community to seek economic or educational opportunities elsewhere, leading to migrations from Djerba to Tunis, France, and Algeria.

Following Tunisian independence in 1956, President Habib Bourguiba adopted a tolerant approach toward minorities, allowing the Jewish community to continue its religious life. However, in 1967, during the fallout of the Six-Day War, anti-Jewish riots broke out, triggering a significant wave of emigration — many Djerban Jews moved to Israel or France in search of security and stability.

Tragedy struck again in 2002 when Al-Qaeda orchestrated a terrorist bombing near the El Ghriba Synagogue, killing 21 people. This attack brought global attention to the community and raised serious security concerns, which subsequently were addressed by the Tunisian government.

Today the Djerba community of about 1,300 preserves ancient traditions and lives with a sense of community and heritage that is rarely seen in the Diaspora. Our group visited the Jewish neighborhoods a number of times. They are home to numerous active synagogues, schools for boys and girls from kindergarten through high school, kosher restaurants and bakeries.

Today the Djerba community of about 1,300 preserves ancient traditions and lives with a sense of community and heritage that is rarely seen in the Diaspora.

One of the things that struck me most when visiting the Djerba community was the utterly natural way in which Judaism was practiced and experienced. There was no pretense or artifice—it was simply the fabric of their lives, the very skin in which they lived.

The sense of community was equally extraordinary. On Friday afternoons before Shabbat, teenagers would arrive at the communal bakery on motorbikes, carrying trays of challah dough prepared by their mothers. These were baked collectively by the entire community in preparation for Shabbat. Later in the day, they returned with their families’ hamin—the traditional Shabbat stew—which was placed in the communal oven on Friday afternoon and retrieved after synagogue services on Shabbat morning to be eaten for lunch.

About half an hour before Shabbat, the chief rabbi walks out to the public square and blows the shofar to announce its arrival. This beautiful custom dates back to the time of the Second Temple, when one of the priests would stand atop the Temple walls and blow six trumpet blasts to signal the people to close their shops, cease work, go home, prepare for Shabbat, and light their candles.

We visited the kindergarten, where the children were in the midst of reciting the Shema. The little girls wore traditional headscarves, like those worn by married women, and the boys donned miniature tallitot, just like their fathers. In the elementary school, children were studying the Torah—the Five Books of Moses—and translating it from Hebrew into Arabic, using the 10th-century translation of Rabbi Saadiah Gaon, known as the Tafsir.

At the boys’ high school, students were engaged in Talmud study, following the unique Djerban tradition. They first explored the Talmudic texts without commentaries, developing and articulating their own understanding of the ideas, which they then presented and debated with their teacher. Only after this process would they consult the commentaries of Rashi and Tosafot. They also devoted time each day to the study of responsa literature, gaining practical knowledge of Jewish law and developing familiarity with traditional rabbinic questions and answers. Although the girls' school was on vacation during our visit, we toured their beautiful new building. The interior—with its posters and decorations—reminded me of the Bais Yaakov girls’ high school in Passaic, where I live, except that the primary languages were Arabic and French.

There are several kosher restaurants and snack stands in the community, so I was able to try a local traditional delicacy, called brick—a thin, round pastry filled with egg, parsley and spices, then deep-fried in olive oil.

There are approximately 50 shochtim (ritual slaughterers) in the community, many of whom regularly travel to larger Jewish communities to perform kosher slaughter. The shochtim of Djerba are renowned for their expertise and their uncompromising adherence to halachic standards. Additionally, there are numerous scribes in Djerba who produce and export Torah scrolls, tefillin, and mezuzot to Jewish communities around the world. Many of the Jews in Djerba are engaged in the trade of gold jewelry, and they enjoy an excellent reputation among the local population for their honesty and exceptional craftsmanship.

As previously mentioned, Tunisia was home to many great Torah scholars, and numerous revered sages are buried there. We visited two of the cemeteries to pray at the gravesites of some of these distinguished figures. Many of these scholars wrote books that are still studied, many established customs that are still observed and many have descendants living deeply Jewish lives in Djerba.

This embodies the spirit of the Jewish community of Djerba. This is a community that has existed for over 2,000 years and remains vibrantly alive, faithfully preserving the ancient and beautiful traditions of our people on a relatively isolated island off the eastern coast of North Africa.

We do plan on returning to Djerba, and if you are interested in joining us for future tours contact Miriam Schreiber at [email protected] or on Instagram: @Miriamslegacykoshertours.

Add me to yout mailing list and the interest group for a fuiture trip to tunisia.

Will do

Best idea would be to contact Miriam Schreiber at [email protected] or on Instagram: @Miriamslegacykoshertours.

Amazing article! Yet another reason why I love Aish. com. I continuously learn new things and am inspired by so many of the articles.

Thank you, glad you enjoyed

Very interesting! Very informative! Very inspiring!

Thank you

A fascinating enlightening article

So happy that you enjoyed it!