Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

12 min read

They helped defeat the Nazis with microfilm tucked into gloves, messages woven into yarn, and intelligence smuggled by bicycle, ski, sewing needle, and hair ribbon.

During World War II, as more than 127 million Allied men and women mobilized across continents, one of the war’s most daring efforts unfolded far from the front lines. It belonged to Winston Churchill’s clandestine “secret army”—the Special Operations Executive (SOE)—a network built to strike the enemy from within.

Among its most effective operatives were women. Operating in occupied Europe, they carried out missions as spies, couriers, wireless operators, and saboteurs. Their work was indispensable: gathering intelligence, disrupting German operations, and bolstering resistance movements under constant threat of capture, torture, or execution.

Operating in occupied Europe, 39 extraordinary women carried out missions as spies, couriers, wireless operators, and saboteurs.

Officially created to “coordinate, inspire, control and assist the nationals of the oppressed countries,” the SOE operated from 64 Baker Street in London. Nicknamed the “Baker Street Irregulars,” agents trained in everything from sabotage and reconnaissance to forging documents and sending covert radio transmissions. They were taught to crack safes, concoct invisible ink from everyday materials, slip itching powder into enemy uniforms, and alter their appearance so convincingly they could pass as elderly villagers or infirm travelers.

Fluent in local languages and able to blend seamlessly into crowded streets and rural hamlets alike, these operatives smuggled intelligence, trained resistance fighters, and carried coded messages across borders—often alone, always unarmed, and frequently on a bicycle.

Historians count 39 extraordinary women among Churchill’s secret army. Here are profiles of a few intrepid women who helped change the course of the war.

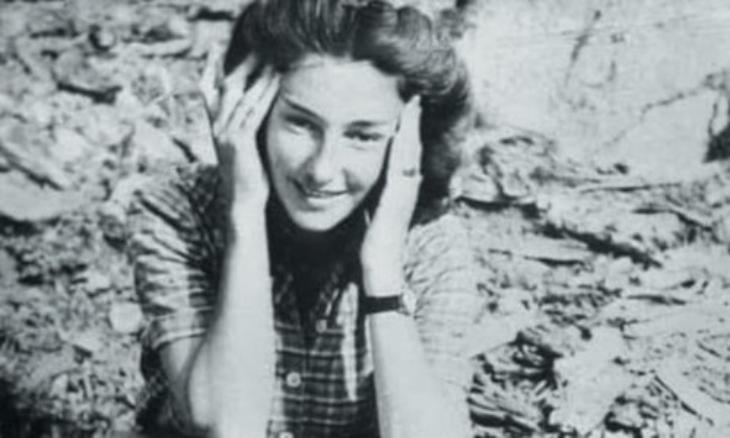

Maria Krystyna Janina Skarbek, born in Warsaw in May 1908, was a Polish countess and the daughter of Count Jerzy Skarbek and his Jewish wife, Stephanie Goldfelder. Raised amid privilege, she enjoyed the luxuries of upper-class life from an early age, often spending her days on a country estate where she learned to ride horses and handle firearms.

She wasn’t only Britain’s first female special agent—she also became the nation’s longest-serving operative, regardless of gender. Her MI6 personnel file from December 1939 described her as a “flaming Polish patriot… expert skier and great adventuress, she is absolutely fearless.”

Early in the war, she proposed an outrageous plan: to ski through the Carpathian Mountains in Hungary into Nazi-occupied Poland to gather intelligence for the Allies. She reasoned that skiing into Poland was simply the fastest way to get there.

In February 1940, she set her daring plan in motion. Braving frozen mountain passes, she skied into enemy-occupied territory, boarded a train to Warsaw, and contacted the Polish resistance to collect critical intelligence for the British. She delivered vital information—including German troop counts, the seizure of Polish assets and industry, and intercepted radio codes and cipher books.

Another bold undertaking followed when she delivered a key roll of microfilm to British intelligence in Bulgaria. Concealed in her glove, the film carried immense military importance. It revealed the buildup of hundreds of German tanks and troops along the Nazi-Soviet wartime border, as well as critical movements of fuel and ammunition—clear evidence of an impending invasion of the Soviet Union. The footage was delivered directly to Winston Churchill.

Parachuting into German-occupied France, she sabotaged Nazi weapons at a prisoner camp and masterminded the escape of 60 Polish captives.

In July 1944, she parachuted into German-occupied France as a courier for the Allies. Within weeks, she had sabotaged Nazi weapons at a prisoner camp and masterminded the escape of 60 Polish captives. Her official citation praised the mission as “not short of remarkable” and “of the greatest value to the Allied cause.”

Skarbek’s most legendary solo operation came soon after her parachute mission. Learning that three senior Allied officers had been captured and were slated for execution the next day, she bicycled 20 miles to the prison, strode in unannounced, and demanded to see the commanding officer. Posing as a British agent—and the niece of General Montgomery—she warned of an imminent American advance and promised to speak favorably of the prison governor if he released the men. If not, she said coolly, he’d be hanging from the nearest lamppost by morning. Her outrageous bluff worked, and the men were released.

Her audacious feats—more like scenes from a spy thriller than real life—earned her the George Medal and an OBE from the British, and the Croix de Guerre from the French, who recognized her extraordinary courage.

Her OBE citation summarized her trip to Poland carrying sabotage material, cash, and mail: “The routes she took over the mountains were of the most arduous description. On one occasion… she walked for six days through a blizzard in temperatures as low as 30 degrees below zero. In this blizzard more than a dozen Poles lost their lives while attempting to cross into Hungary.”

Noreen Riols was just 17 when she joined the SOE to train British agents and support the French Resistance. Fluent in French but too young to be deployed in the field, she was given a crucial role in helping select—or disqualify—appropriate SOE candidates.

Riols was born in Valletta, Malta, where her father served with the Royal Navy. She later attended the Lycée Français in London, becoming fluent in French. Upon joining the Special Operations Executive, she was assigned to its French section, which prepared agents for missions in occupied France and coordinated with the French Resistance. There, she observed the debriefings of operatives who had been exfiltrated—men and women who had spent every waking moment evading the Gestapo.

“For me it was a revelation to see their different reactions,” she recalled. “Some returned with their nerves absolutely shattered, in shreds. Their hands were shaking uncontrollably as they lit cigarette after cigarette. Others were as cool as cucumbers. Many of those agents weren’t very much older than I was. Hearing their incredible stories, witnessing their courage, their total dedication—I changed almost overnight from a teenager to a woman.”

Her primary role was to train officers in surveillance by serving as their target during exercises. In their final test before deployment, she acted as a “honey trap,” attempting to charm agents into revealing their mission—an essential measure of their discretion under pressure.

Years later, she wrote, “The training exercises taught future agents how to follow someone, how to find out where they were going, who they were seeing, without being detected. How to detect if someone was following them and throw them off. How to pass messages without any sign of recognition.”

One of her favorite ways to shake off the male trainees tailing her was to duck into the ladies’ lingerie section of a local department store. The bewildered men trailing behind her drew curious stares from shoppers and clerks alike. “I’d hold up a few unmentionables,” she recalled, “just to make them squirm a little more.”

After the war, Riols joined the BBC and went on to publish eleven books. In recognition of her contributions, she was named a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur by France in 2014 for her work preserving the memory of the 104 SOE agents who lost their lives in occupied France. Nearly a decade later, she was honored with an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire).

Odette Sansom became a key figure in the D-Day liberation of Normandy and Western Europe—but her involvement began almost by accident.

In 1942, the British Admiralty issued a public appeal asking civilians—especially those with ties to France—to send in postcards or family photographs taken along the French coastline. These images would help the military analyze terrain and coastal defenses in preparation for future operations, including potential landings and sabotage missions.

Odette, a French-born housewife living in Somerset, responded. She had taken photographs along the coast but mistakenly sent them to the War Office instead of the Admiralty. Her letter caught the attention of the SOE, who saw potential in her fluency in French, familiarity with the region, and evident patriotism.

She accepted the SOE’s invitation to join them—French by birth but loyal to the Allies and married to an Englishman.

Once she entered the organization, Sansom underwent intensive training in self-defense, Morse code, parachuting, survival behind enemy lines, and resisting interrogation. To legitimize her presence in France, the SOE enrolled her in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, a British all-female charity that provided credible cover for her covert work.

Under the identity “Agent S.23” and the codename “Lise,” she was deployed to occupied France, where she served as a courier, built resistance networks, and gathered critical intelligence—constantly evading the Gestapo.

Though her training reports criticized her as “excitable, temperamental, impulsive and hasty,” and “unwilling to admit she could ever be wrong,” they also praised her “patriotism, determination, and keenness to do something for France.” She was eventually cleared for duty and deployed to join SPINDLE, an SOE network in southern France tasked with coordinating resistance efforts and intelligence gathering. She ultimately became Winston Churchill’s personal courier. One of her first missions was establishing a safe house for British agents traveling through Paris.

When the leaders of SPINDLE were captured, Odette faced the Gestapo 14 times. Each interrogation brought new torture; each session was a brutal attempt to break her silence. But Odette never wavered. To every demand, she offered the same quiet reply: “I have nothing to say.”

Even when sentenced to death—twice—she met the verdict with unflinching wit. “Then you’ll have to decide which charge to use,” she said. “I can only die once.”

Odette was eventually deported to Ravensbrück, the notorious women’s concentration camp. There, she endured brutal conditions—confined to a punishment block, often in solitary confinement. At one point, she spent three months and eleven days alone in total darkness.

Her resilience never faltered. Claiming to be a relative of Winston Churchill, she caught the attention of a German officer who, sensing the war’s end, handed her over to American forces in 1945 in hopes of securing clemency. Odette not only accepted his surrender personally but later testified against him at the Nuremberg Trials.

She became a highly decorated war hero and public figure, earning an Order of the British Empire (Member) and the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest decoration. In 1946, she became the first woman to be awarded the George Cross—the United Kingdom’s highest civilian award for bravery—for acts of exceptional heroism in extreme danger. She accepted the award on behalf of all her fellow agents who did not survive.

Her life story was later told in the 1950 film Odette, starring British actress Dame Anna Neagle, and in 2012 the Royal Mail issued a stamp in her honor.

Phyllis “Pippa” Latour Doyle, who died in New Zealand in 2023 at age 102, was the last surviving female agent of Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE). Born in South Africa in 1921, she was orphaned at four and raised by an uncle in the Belgian Congo. Multilingual—fluent in English, French, and several African languages—she studied in Kenya before moving to Europe in 1939.

She joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force in 1941 but found the work dull. In 1943, she volunteered for the SOE, training in parachuting, wireless communication, weapons, and hand-to-hand combat. Her escape and evasion lessons came from an unusual source: “A cat burglar was taken out of prison to train us,” she recalled. “We learned how to get in a high window and down drainpipes and how to climb over roofs without being caught.”

Latour excelled as a wireless operator and was deployed to occupied Normandy in May 1944 under the codename “Genevieve.” Disguised as a teenage girl, she cycled through the region selling soap to German soldiers—gathering intelligence through casual conversation. “The men who had been sent just before me were caught and executed,” she said. “I was told I was chosen for that area because I would arouse less suspicion.”

Working with the Resistance, she transmitted 135 coded messages to London, pinpointing enemy troop movements and supply routes that guided Allied bombing runs and supply drops ahead of D-Day. To hide her codes, she wrapped silk strips around knitting needles and tucked them into a shoelace she wore as a hair tie. “I always carried knitting,” she explained. “I had about 2,000 codes. When I used one, I’d pinprick it to mark it gone.”

She also sabotaged German infrastructure, cutting underground telegraph cables and disabling the railway between Paris and Granville. Her unit’s report on an SS Panzer division enabled Allied aircraft to destroy 500 enemy vehicles.

Her courage and effectiveness earned her the Member of the British Empire (MBE) and France’s Croix de Guerre. After the war, she settled in New Zealand, where her legacy was later honored with the Legion of Honour in 2014 and a street named “Genevieve Lane” in 2020 at a former Royal New Zealand Air Force base.

The tales of the SOE’s “irregular” women go beyond gender—they are powerful human narratives of bravery, boldness, and selfless devotion.

Sources

Amazing. Thank you! If Skarbek's mother was Jewish, she was Jewish. I wonder if she was raised at all as such. Next week I am bringing tourists to the fabulous museum "Jewish Soldiers in WW2" Museum at Latrun. I will ask if they have her in their records.

in case you missed my previous article, check out https://aish.com/jewish-americans-who-were-awarded-the-medal-of-honor/

I loved reading about these brave and fearless women who helped the causes of our Allies during WWII. This is the first time I have read an article about these women and thought the writing was very well done. It has inspired me to read more about this subject. Very well done and thank you!

Thank you for the kind words, Leslie. So glad you enjoyed this and it sparked your further interest in the amazing subject.

Not sure why, but Mr. Rich did not mention Virgina Hall, a well know SOE member who was an American and who is the Subject of the book entitled "A Woman of No Importance". Amazing life and riveting book.

Thank you for mentioning this information

Thank you for the feedback, Renee. If we ever write a "Part Two" we'll take a look at Virginia and some of the other 34 SOE women.

My mother's brother married a lady who was engaged before the war to Isaac Newman a Jewish SOE operative who was captured, interrogated and killed in France in 1944.

That's a great tidbit of information, Simon!! Thanks.

I am never disappointed in the stories from Mr.Rich. I say this each time, but this one may be my favorite.

Thank you Mr. Crowder. How amazing were these women?