Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

8 min read

What is the definition of “rabbi” and how do you become one?

A rabbi is a Jewish scholar, and an expert in one, or even many, areas of Jewish wisdom and thought. He may serve in an official capacity as a community leader, teacher, or judge; as an impartial, and mutually agreed upon, arbiter of disputes; in an administrative capacity in any number of Jewish communal institutions; provide oversight in complex, difficult areas involving the intersection of industry and Jewish law (like the kosher industry); render life and death decisions in medical cases; and myriad other responsibilities.

But many rabbis also do not hold official positions, yet are still sought out for guidance and advice, publish voluminous works, distribute gifts to the poor, consult with important political leaders, and assume an informal leadership role in community affairs.

In the modern era, rabbis have also taken on numerous pastoral responsibilities, and nowadays officiate at weddings and funerals, prepare youngsters for their bar and bat mitzvahs, deliver sermons at Sabbath and High Holiday services, and perform many other duties of contemporary clergy.

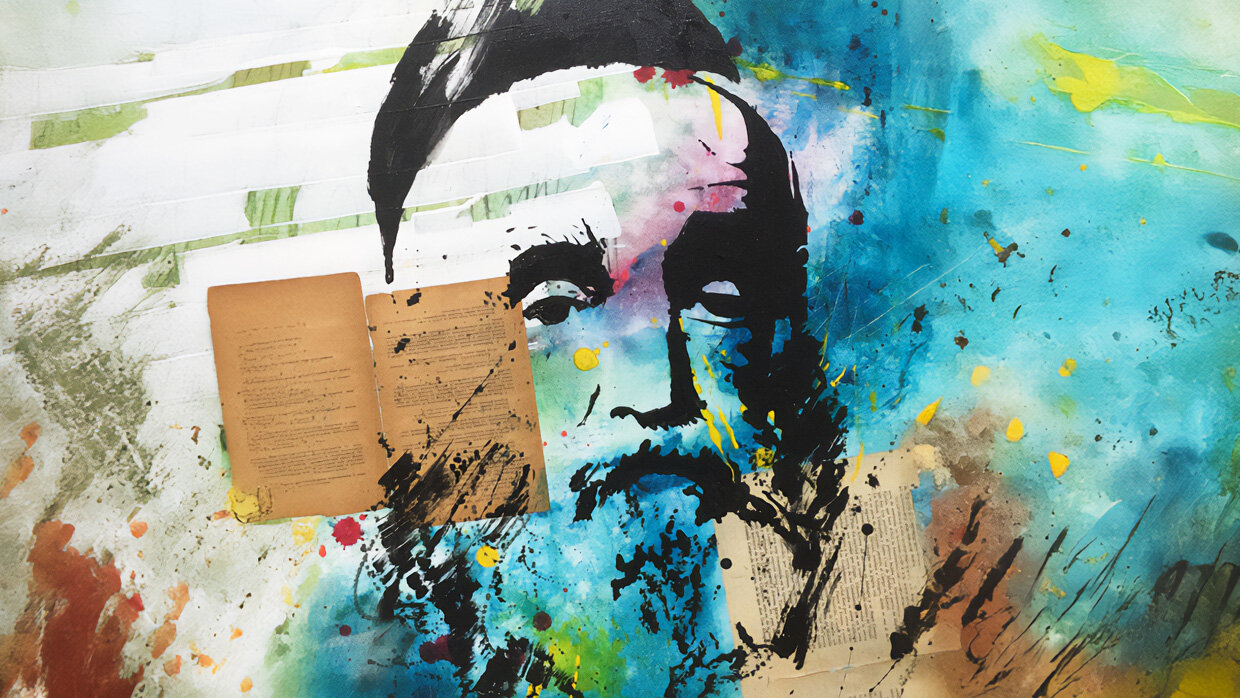

Rembrandt’s Old Rabbi

Rembrandt’s Old Rabbi

A rabbi is an important leader and mentor, and someone to look to for guidance and advice. According to the Talmud,1 every person—even a great leader—needs a rabbi to talk to, to render impartial judgments, and to help you work through life’s many challenges.

The word “rabbi” means “great” or “revered,” and was first used the way some people use titles like “master” or “lord.” The term does not appear until the first century of the common era, and is not used in the Hebrew Bible. The earliest Jewish leaders and teachers did not have titles, and were often just known by their names—like Abraham, Moses, Hillel, and Shammai—but in later years, especially during the Roman occupation of Judea (which started in the last century before the common era), Jewish people began using ”rabbi” as a way to refer to their scholars and leaders.

Variations of the term include Rabban, which refers to some leaders of the Sanhedrin, or high Jewish court; Rebbi, which, as it’s used in the Talmud, refers specifically to rabbis ordained in Israel; and Rav, the Talmudic title for rabbis ordained in (what the Talmud refers to as) Babylon, or modern-day Iraq.2

Modern usage of the term includes Rebbe, which may refer to the dynastic leader of a Hasidic community, although it is also used as a less formal way to address a teacher; Reb, which many use as a substitute for Mister (although it often precedes a person’s first name); Rav, when referring to a distinguished or important rabbinic figure; as well as the more generic and ubiquitous, Rabbi.

The concept of the rabbinate—a collective rabbinical body with the power to make decisions and pass decrees—starts in the Second Temple period (350 BCE - 70 CE), with the men of the Great Assembly, and subsequent rabbinical courts.3 The idea of the court itself is of biblical origin, and dates back to the days of Moses,4 although its power—as well as the role of, and the usage of the term, “rabbi”—began to evolve in the first century, and as a reaction to Roman rule.

In Talmudic times, under pre-Islamic Persian rule—in what is today Iraq—Jewish communities were somewhat autonomous, and local rabbis judged civil cases, issued decrees, set community standards, and interacted with the non-Jewish authorities; in addition to their traditional roles as teachers and spiritual leaders. Following the period of the Gaonim (the last 500 years of the first millennium), some writers started to use the term rabbanim (רבנים), or rabbinate, to refer collectively to that era’s rabbinical leaders. At that time, Jewish religious authority was still somewhat centralized, and the title was a way to distinguish mainstream Jewish leadership from a growing heretical Karaite minority.5

Up until the Enlightenment, emancipation, and the dawn of the modern era, Jewish communities were given varying degrees of self-governance, and local rabbinical authorities arbitrated disputes, rendered legal decisions, and helped with general communal oversight in addition to their more spiritual concerns. Modern governments, however, are more hands-on, and are, in general, their nation’s sole legal authority, which has diminished the role of the rabbinate, although not in areas ceded to clergy, like conversions, circumcisions, funerals, weddings, and the like.

In modern Israel, the office of the Chief Rabbi—Israel’s first Chief Rabbi was Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, who took the position in 1919—oversees much of the nation’s religious concerns, including kosher supervision, determining and verifying a person’s Jewish lineage, overseeing conversions, maintaining rabbinical courts, granting rabbinic ordination, and other civic responsibilities.

The concept of rabbinic ordination derives from the book of Numbers (27:18-23), when Moses invested his successor, Joshua, with the authority to lead the Jewish nation. “God said to Moses, ‘Take Joshua son of Nun, a man of spirit, and lay your hands on him. Have him stand before Eleazar the priest and before the entire community, and let them see you commission him’ … [Moses] then laid his hands on [Joshua] and commissioned him.” The term for rabbinic ordination, semicha, which literally means “support,” is taken from that verse — “lay your hands on him”—as well, and symbolizes the continuous Jewish chain of transmission. According to Jewish tradition, ordination was done from an ordained rabbi to his student, and that process continued until the end of the Talmudic period, about 1700 years later, when it fell into disuse, likely due to Roman oppression.

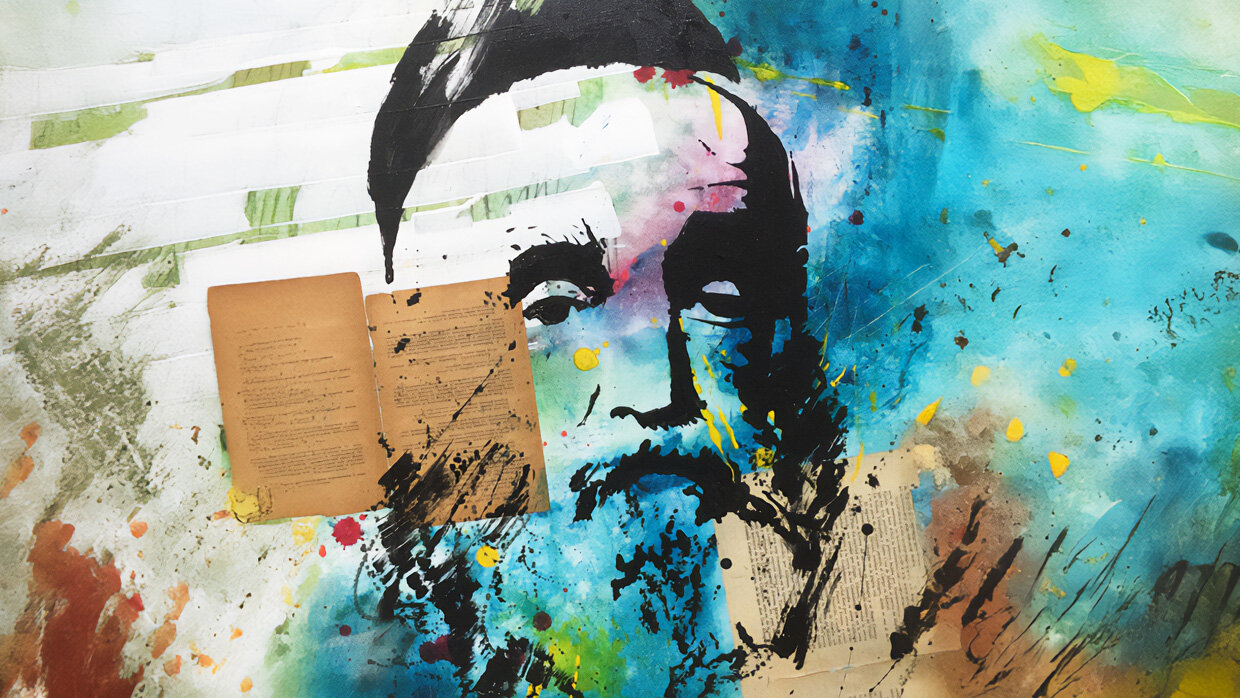

The Chafetz Chaim, by Igal Guinerman

The Chafetz Chaim, by Igal Guinerman

That type of ordination does not exist today, and rabbis do not have true authority invested in them as in the past. However, modern institutions often have their own ordination programs to ensure their graduates qualify for rabbinic positions. Rabbinical schools (yeshivas) do not have universal standards, and some institutions are more rigorous than others, but in general semicha minimally ensures that a rabbi can render a decision in basic matters that concern the intricacies of kosher food. In Israel, the Chief Rabbinate has a comprehensive program for ordination, which contains several different levels of ordination that qualify a scholar for different types of rabbinical positions.6

According to the Talmud,7 every person needs to forge a relationship with a leader or mentor. That person—a wise man, your rabbi—will guide you through the complexities of life.

To do that on a practical level: find someone who speaks your language, who gives you meaningful answers to your questions, and invest in that relationship. Ask more questions, test his wisdom, and get to know each other. In addition to possessing insight and wisdom and being someone you respect and can communicate with, a good mentor must also inspire trust. You want to choose someone who understands you, and who knows your background and family history. You also want to find someone who will challenge you, and who will push you to fulfill your potential. Don’t choose someone who allows you to make rationalizations, or who doesn’t really believe in you.

Featured image by Igal Guinerman. Click here to visit his gallery.

What is the title of the other picture, of the rabbis discussing, unfortunately a bit out of focus? I love it, you can just imagine the dialogue!

Well done!